|

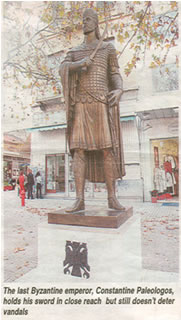

Tales of Athens’ Stoic Faces Athens News Harry S. Truman’s woes, Theodoros Kolokotronis controversial helmet and Constantine Kanaris’ vanishing arms are among the stories to have emerged during restoration work on the capital’s often neglected monuments By John Hadoulis Ever since its installation in the mid-sixties, the statue honoring America’s 33rd president has been blown up, smeared with paint, wrapped for mock dispatch to the States and eventually given its own armed guard, ahead of President Bill Clinton’s visit to Athens in November 1999. For his part in bankrolling the government during the 1945-49 Greek Civil War, Harry S Truman has made few fans among the Greek left. The crew that restored his statue to its pedestal after it was last toppled in 1999 even had to work under cover of the darkness, just in case. “It was a commando-style operation, carried out with riot police present,” recalls a participant, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The Athens municipality wanted as little involvement as possible. Even the crane we used came from the fire department.” A year later, the statue of Truman’s Secretary of State George Marshall would spark a more serious attack against sculptor Theodore Papagiannis, whose workshop was damaged by a makeshift bomb. The fact that Papagiannis had also created the Communist Party’s hammer-and-sickle-baring statue for its Perissos headquarters didn’t appease the attackers. Kolokotronis’ divisive helmet Even in the case of statues without recent political baggage, there is no shortage of tales coming out of Athens’ departments for architecture and roadworks, the two municipal authorities overseeing statue restoration and installation. Some involve little-known tidbits which resurface by coincidence, such as the old controversy surrounding the crested helmet of Independence War hero Theodoros Kolokotronis. During restoration working 2001 on the equestrian statue which dominates upper Stadiou St., the conservators found etched on the helmet’s inner rim revealing that sculptor Lazaros Sohos preferred Kolokotronis bareheaded. “Against the wishes of Sohos, my dear Kolokotronis, place your helmet back on,” it reads. “From Sohos’ correspondence, we know he considered the helmet to be part of the uniform Kolokotronis wore when he enlisted in the British army, and the sculptor saw it as non-Greek,” says Zetta Antonopoulou, an archaeologist and restoration specialist working with Athens’ architecture department. Kolokotronis briefly served with the British army in the Ionian islands during the Napoleonic Wars. He joined a special Greek light infantry unit wearing British dragon-style helmets and Greek kilts. Goalkeeping Kanaris Another Greek Independence War hero, the intrepid fire ship captain Constantine Kanaris, required more immediate attention last summer, when the arms of his statue on Kypseli Square slowly started to disappear. “The strange thing was that his fingers were the first to go, followed by the wrist and then the forearm,” said Antonopoulou. The loss of Kanaris’ arms to football kicks is probably an exception among the usually deliberate forms of damage dealt to Athens’ statues. The Monument of Youth, the statue of a young man that used to stand on the junction of Kallirois and Vouliagmenis avenues, carries a bullet marks on its chest, probably from the time it was located outside the Cadet Academy. And both the statues of Independence War general Yiannis Makrygiannis and Constantine Paleologos, the last Byzantine emperor, have had their swords targeted by vandals. Makrygiannis’ weapon has been snapped at the hilt on several occasions, while Paleologos’ was bent backwards a few years ago. But such cases of physical exertion are rare. Nowadays, the practical football hooligan or street protester rarely leaves the house without a handy can of spray or marker. A 2000 conservation survey found that a fifth of Athens’ outdoor bronze monuments carried graffiti marks. Dr. Vasilike Argyropoulou of the Athens Technical Education notes in a 2004 paper on the need for a public awareness campaign to prevent vandalism. Marble is even more popular, says the metals conservation expert, given that graffiti has better exposure on it. “It’s like a big white canvas, and they love it,” she says. Vandals under the sun Though Athens is fortunate to escape pollution-related maintenance

problems plaguing other European cities, says Argyropoulou, it has

serious vandalism trouble. And the fact In her paper, Argyropoulou observes the disparity between monuments and churches, which are rarely marked. “I raised this question during a discussion with a group of high-school students…I was enlightened when one student said that young people feel a connection with their church, but for many of the monuments in the city, they did understand their meaning or significance in their lives.” She writes. Nevertheless, municipal staff are occasionally heartened by the response of local residents to vandalism incidents. In Paleologos’ case, the municipality was alerted by neighboring shopowners, and one of Greece’s rightwing nationalist organizations later sent a representative to ask about the statue’s fate. In Makrygiannis’ case, residents of the area – which has been named after the general and where his family house still stands – helped crews reattach the sword. “They really love that statue,” says Antonopoulou. “I’ve never seen it without flowers in its hand.”

|

The conservators

eventually found their explanation among the children who play football

on Kypseli Square, just beneath Kanaris’ beckoning arms. The

statue got a new pair of arms, attached with titanium pins and special

glue.

The conservators

eventually found their explanation among the children who play football

on Kypseli Square, just beneath Kanaris’ beckoning arms. The

statue got a new pair of arms, attached with titanium pins and special

glue. that

the city lacks a full-time maintenance program doesn’t help

either, she adds. “We have less corrosion (from the acid rain),”

she told the Athens News. In countries such as Finland and Sweden,

the monuments look green and corroded. Our big problem is vandalism.”

that

the city lacks a full-time maintenance program doesn’t help

either, she adds. “We have less corrosion (from the acid rain),”

she told the Athens News. In countries such as Finland and Sweden,

the monuments look green and corroded. Our big problem is vandalism.”