|

|

|

Athos: Mystical Spirituality Meets Conservatism by George Gilson |

|

|

0 sages standing in God's holy fire Sailing to Byzantium, William Butler Yeats |

|

|

Like all that penetrates to the core of the religious sensibility, the 1000-year-old monastic colony of Mount Athos is a paradox. Humility is a paramount aim in Orthodox monasticism, but the Athonite monks are the most vitriolic critics of other Christian confessions and view even joint prayer with Catholics as condemnable heresy. Athos is dedicated to the Virgin Mary and is called the "garden of the Panaghia," but women are banned from the peninsula. The monks have traditionally been xenophobic-opposing Greece's entry into the European Community in 1980, but happily absorbing tens of millions of euros in ED funds since. Athos has been considered one of the major repositories of Greek culture, but here the monumental pre-Christian achievements of Hellenic culture are eschewed as foreign. I first visited Mount Athos in 1981, and it was like a journey in a time machine. The 45-minute boat ride from the seaside Chalkidiki town of Ouranoupolis to Athos' main port of Daphne was truly a journey to Byzantium. The creaky, decades old bus that tugged you up the rugged dirt road to the capital of Karyes was one of the only reminders of frenzied modernity in the gorgeously verdant environment of the peninsula. The worn stone-paved footpaths were the only route between the 20 major monasteries and smaller sketes and cells. You reached your destination by sunset, to be led to barrack-like guest rooms with six to twenty beds for a few hours' sleep, before a monk's beating of wooden simantron in the courtyard awakened monks and pilgrims, so that they could flock to church services in the middle of the night. There, the oil lamps and candles were the only light shining on the dimly lit Byzantine wall murals of saints and martyrs, darkened by centuries of incense. The plaintive chanting of the cantors was punctuated by the rustling of the black cassocks of barely visible monks, scampering to venerate all the icons before repairing silently to their worn wooden seats lining the walls. The winds of change Four journeys and a quarter century later, in October 2004, much has changed on the Holy Mountain. Broad cement roads have sprouted in many directions, and electrical lighting in well-appointed guest rooms are par for the course. For many visitors, a fleet of vans driven by monks and lay workers have replaced the footpaths as the means of choice to travel between monasteries. The 10th century founder of communal monasticism on Athos, Saint Athanasios the Athonite, solidified a long history linking the monastic peninsula to Byzantine Emperors when Emperor Nicephoros Phocas sent him to found the Megiste Lavra monastery, still the first in rank on Athos. In 885, Emperor Basil I had issued an edict devoting the peninsula to the monks, who had repaired there at least from the 8th century iconoclastic controversy. Athanasios' project brought the first outcry against grand and commanding buildings, and some monks today cite him as a precedent to justify the current construction outburst. His fame brought a flood of monks from throughout the empire, from Calabria to Armenia. The architectural structure and coenobitic (communal) typikon (monastic rules) of Megiste Lavra were a model copied by many of the subsequent monasteries, though over the centuries many abandoned the communal model for the idiorythmic (in which monks ate, worked and often worshipped independently). The communal arrangement was made mandatory just over a decade ago. |

|

|

A monk's mission The repentance, spiritual discipline and contemplative prayer through which the monk strives to see the light of God, was articulated by the 14th century Saint Gregory Palamas, a Constantinopolitan who was a monk on Athos before serving as Archbishop of Thessaloniki. His hesychastic philosophy (from the Greek word for quietude) included treatises on why the prophet is better equipped than the philosopher to understand God. Hesychastic prayer was considered its own higher form of philosophy as far as the pursuit of God was concerned, which helps in part to explain (in addition to their lack of academic training), the Athonite banishment of ancient learning. |

The massive Russian Saint Panteleimon Monastery's ultrconservative can be unwelcoming to visitors |

|

Still, curiously, one finds wall paintings of ancient philosophers such as Socrates and Plato at some monasteries, such as Vatopedi, incorporating them into their own conception of "Greek-Christian" culture. Indeed, Athas' libraries have through history been repositories for rare copies of ancient writers, many of which were sold by monks to Western rulers ,and other enterprising scavengers over the centuries. |

|

|

The Greeks have had their share of monks whose reputation as men of learning and influence extended far beyond the Holy Mountain. Saint Nikodimos the Athonite in the 19th century became well known for his systematic exposition of the church canons, but also was part of a long line of accomplished Athonite hymnograhers who wrote services honouring saints in Byzantine musical notation, of whom the last was Gerasimos of Small Saint Ann's skete. Priest Evgenios Voulgaris-a key Greek enlightenment intellectual who wrote on logic, metaphysics and astronomy, translated political philosopher John Locke and served as librarian to Catherine the Great - taught at the Holy Mountain's Athonias school from 1753-1759. But his enlightenment theories irked the monastic bigwigs who pushed him out. The school now operates as a religious high school (since 1953) and has students from Greece and other countries. The monks' dogmatism has often placed them at loggerheads with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which exercises spiritual jurisdiction over Athos, particularly over its 1923 acceptance of the Gregorian Calendar and its more recent theological dialogue with the Catholic Church. Patriarch Athenagoras was condemned in a 1971 pamphlet by Athonite monks for his contacts with Pope Paul VI, with whom he lifted a mutual 900-year-old excommunication in 1964, and for allegedly espousing a syncretist view (reconciling different belief systems) rather than defending the absoluteness of Orthodox truth. Athenagoras and subsequent patriarchs were long not commemorated at Athonite services. My most recent journey begins at the huge monastery of Saint Panteleimon. The sheer size of its buildings testifies to the fact that it once hosted around 2,000 monks. The massive late 19th century influx of Russian monks was connected to Moscow's geopolitical aspiration to gain access to a crucial warm water port and created strong conflicts with Athos' Greek Orthodox majority. The 1917 Russian Revolution stemmed the flow, as new monks were allowed to come only to replace those that had died off. Even today, there is said to be a strict Greek state quota on the number of monks allowed to come. Athos insiders describe deep conflicts and a power struggle between the Russian and Ukrainian monks, who now constitute the majority. A lay worker says that the Ukrainian government has pledged $6 million to rebuild the shell of a huge, decrepit building as a hospital for the 70 monks. They have already completed a massive garage right by the waterfront. About 30 workers of the Thessaloniki based Athoniki Techniki construction company live on the premises, seven Greeks and the rest from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. One lay worker speaks of the detailed preparations weeks before for a visit-later cancelled-by Russian President Vladimir Putin. About 20 Russian secret service agents with 50 crates of security equipment swarmed the monastery and surrounding area for two weeks. |

|

|

|

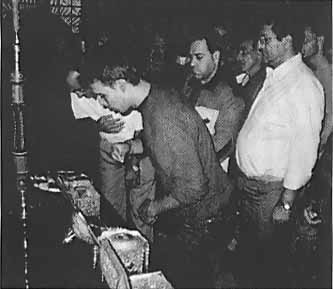

Visitors view and venerate saints' relics, Athos' most cherished treasures |

|

While Makarios grants me permission to photograph the impressive buildings, the Russian Filosof defiantly insists that a "Sobor" (monastic council) decision is required. En route to the matin service at 2am, I attempt to capture a photo of the full moon above the guest house onion dome, outside the monastery. Suddenly, out of the darkness, Filosof rushes at me and attempts to pull my camera away. When I resist, he tries to shove me toward the guest house and orders me to lock the camera in my room. He shouts that he will call the police if he sees it again. A smaller brotherhood The next stop is the skete (small monastic community) of Bourazeri, where a middle-aged monk named Arsenios is the Elder, rules over a brotherhood of 30 with an iron fist. One monk even requires his blessing to make a phone call. The skete boasts a fine iconography workshop with eight self-taught monks, while a novice works on religious mosaics. Crafts and handiwork are the main source of income for the smaller monastic brotherhoods. Bourazeri has undergone extensive renovation and building with its own funds (they are among the few who refuse EU money), and the spanking clean and colourful texture of the buildings has something of a Disneyland air about it. The ambitious Arsenios-who with his retinue launched a failed attempt in the 90's to take over the leadership of Megiste Lavra-admits that they did not consult an architect or engineer for the works, and that the pastel colour schemes and protruding wooden balconies reflect "their own aesthetic." Archaeologists insist that such arbitrary interventions allover Athos have helped destroy its unique architectural heritage. I continue on to Osiou Grigoriou monastery, a vibrant brotherhood of 80, which is led by Abbott George Kapsanis, widely reputed in Greece as an intellectual theologian. As I arrive, dozens of monks gather to see him off for a trip to Patras for knee surgery. He is carried with pomp and ceremony seated on a Papal-style stretcher with a crimson pillow, as he can barely walk. He greets me in English-"welcome"-and a broad grin peering out of his plump, grey-bearded visage. Father David, a red-haired baby-faced monk receives visitors and asks if anyone wants to go for confession. A whopping 10 out of 30 say yes, and eight ask specifically for the well-respected spiritual Panaretos, a soft-spoken and non-judgmental 60-year old with 30 years on Athos. Many hundreds of Greeks flock to Athos for confession each year, perhaps confident that their secret is safe on the remote monastic peninsula. The relics of saints and martyrs, from the hand of Saint John the Baptist to the girdle of the Virgin Mary, are the first aspect of Orthodox spirituality to which visitors are exposed at many monasteries, where the monks cart them out to be viewed by visitors. These are kept as the most cherished treasures and are venerated as miracle working. A touch of xenophobia The next day, a 50-something monk named Artemios gives a "lecture" to about 20 visitors. He outlines the history of Athos and monasticism before stressing the monks' goal of fighting the urge for money, glory, and pleasures of the flesh. Asked how Christians should deal with charity, he stuns visitors by denouncing Doctors Without Borders and UNICEF as "Masonic organizations." To make his case, he cites a Greek donor who did not receive a reply from Doctors Without Borders when they asked where their money went in Africa. Later, Cypriot monk Neophtos reads to visitors from the sayings of the late Elder Paisios, a renowned prophetic confessor who reportedly could tell a pilgrim his problem before he even opened his mouth. He introduces Christos, a Greek living in Barcelona, who says the church (and Alcoholics Anonymous) helped him get over his alcoholism. Yannis, a 50-year-old former merchant marine, says he visits the monastery every year for several days, and he hopes to become a monk at Grigoriou one day, when he "gets his affairs in order". Certainly, not all aspiring monks who go to Athos stay. One night at about lOpm a 19-year-old novice is restrained by two monks after having a shouting fit, cursing at one of the monks. His father died and his mother is dying of cancer, so his aunt sent him to Athos to become a monk. The aunt was called to pick him up a few days later. |

|

|

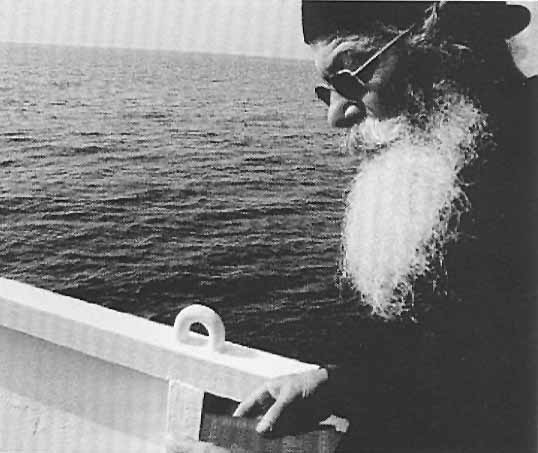

Abbott Parthenios of Agiou Pavlou Monastery, a rugged 73-year-old villager from the Ionian island of Cephallonia, is a prime example of Athos' traditionalist conservatism. |

The summit of the Athos peninsula, Mount Athos, shrouded in clouds, seen from the Bourazeri community |

| An outspoken critic of abortion, he recounts that he was one of nine children, with 35 cousins. When one of his spiritual children became a gynaecologist, Arsenios demanded to know if the doctor had performed any abortions. "I was asked to once, but I refused. I would rather go to jail," the doctor replied, recalling that Arsenios had made him promise not to do anything unethical. But it is the traditionalism of the ascetic philosophy that lies at the heart of the ascetic enterprise on Athos, the quest to overcome the ego and its demands in order to come closer to the divine. Happily, the monks themselves are usually the first to admit that they fall short. In some way, visitors cannot be untouched by that, as they take a step away from the daily rat race to clear the mind and soul of the worry of survival. In this endeavour, much on the Holy Mountain still conspires to help, from the natural beauty to the priceless treasures that make Athos a vast museum of Byzantium and a main repository of Eastern Orthodox spirituality. |

|

|

German Sekt (several authorised varieties) is made by the transfer method. Italian Spumante (White Muscat) is made with the Charmat tank method. Greek sparkling wine from Rhodes (local Athiri grape) is made like champagne in the bottle. Quality bubbly Sparkling wine technology was discussed in a preceding article. This time we'll give a few pointers about what to look for when choosing a sparkling wine. |

Greek pilgrims, amny of whom flock to Athos for confession and spiritual uplifting, break almonds at Grigoriou Monastery for the wheat kolyva, eaten after a memorial service |

|

Secondly, the technique for making them effervescent. Even though both Champagne and Rhodian wine makers employ similar techniques to "add bubbles" and use similar aging methods (18 months in the bottle)-they don't create the same wine. The price isn't the same either. Obviously, bubbly should have good sparkling bubbles. What does that mean? There should be a consistent, steady stream of tiny bubbles moving up from the bottom of the glass in a straight, even line that lasts for quite some time after the bottle has been opened. The wine in the glass should be effervescent. In addition to this aspect, when looking at a glass of sparkling wine it should be brilliantly clear with green tinges. If it looks yellow, brown or flat it has gone bad; its unpleasant aromatic character will confirm this when it is smelled. There is one specific case-Chardonnay-based aged vintage Champagne more than ten years old-where extremely yellow sparkling wine is acceptable. Aromatically, sparkling wine should have evident, though not flagrant, scents that, depending on the grape variety involved in its elaboration, will be floral with a hint of green apples and pears. If it has smoky, bacon or cork tainted characters-send it back-they are defects. Tasting a sparkling wine presents difficulties because the bubbles interfere with aromas and flavours, as well as increase the sensation of acidity. Also, wine makers adjust the sweetness to soften the acidity. But, a good sparkling wine will offer a brief spot of crispiness (attribute this to the acidity) when first swallowed. This should immediately turn into a smooth, creamy texture and finish with a clean, refreshing (the acidity again) taste, making you want to immediately drink more. Try it for yourselves. Gather a few friends. Purchase bottles of Champagne, Spanish Cava, Italian Spumanti, German Sekt and Greek sparkling wine from Rhodes, then compare them using the above parameters. But, make sure that all the sparkling wines have similar amounts of added sugar. They should all be Brut (the driest), Extra dry, Sec or Demi-sec (sweeter).

|

|

|

(Posting date 30 March 2006) HCS encourages readers to view other articles and releases in our permanent, extensive archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com/contents.html. |

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

|