|

|

Most of the churches still standing date from the 11th and 12th century, and many of them rest on much earlier foundations. As might be expected, Christianity had been slow to find converts in this bastion of Classical thought and knowledge. The early emperors tried to eradicate the pagan religions and the schools of philosophy, but even though the center of the world had shifted to Rome and then to Constantinople, Athens remained an important university town revolving around Plato’s old Academy. The first serious threat came in 435 when Theodosius II issued the order to close all the ancient shrines. The Parthenon, with the statue of Athena still in place, was eventually rededicated to the Virgin and the Hephaisteion to St. George. The Christians also started erecting new buildings, outside the city walls. Evdokia, the emperor’s Athenian wife, saw to it that an enormous basilica was constructed near the temple of Olympian Zeus. It was called St. Leonides after an early bishop of Athens but it also commemorated her father Leontius, a sophist philosopher. The lady was obviously torn; though she was a Christian, she respected the old learning. The faculty she later endowed in Constantinople emphasizing Greek rather than Latin scholarship kept the classics alive until the Renaissance.

By the 10th century, Athens was heading back to prosperity. It had as many as ten bishops and, in 1054, some 140 churches. In 1018, Basil the Bulgar-Slayer had a Te Deum sung in the church of the Blessed Virgin – the Parthenon – to praise God for the victory that gave him his homific name. It must be said, however, that he had come to do homage to the defenders of Marathon and Salamis, rather than pay his respects to Pericles and Plato. In any event, Athens appears to have been thriving on profits from Hymettus honey soap, dyes for Theban silks and sculpture, while pilgrims came from all over Europe and the Holy Land to visit the Acropolis and buy relics and souvenirs. Meanwhile the center of Athens continued to be the agora. The market district functioned in more or less the same way from antiquity until the late 19th century. And because we know where various activities were located during the Ottoman period, we can deduce what was going on towards the end of the Byzantine era. The area around Pandrossou and Hadrian's Library was probably the so-called Upper Bazaar, where there may have been storehouses for agricultural products; the steps off Pandrossou and into Monastiraki formed the Lower Bazaar, with the fabric and tanning industries, the ironmongers and coppersmiths – which are echoed in today's shops – and the barbers, cutting hair on the steps. The Roman Agora seems to have been the place where salt, olive oil and wheat were traded, using the original Roman weights until the late 17th century.

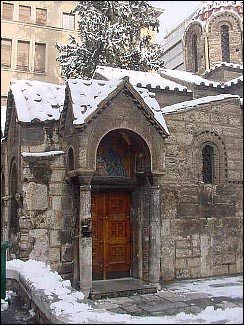

The city's Byzantine churches are concentrated around Plaka with just a few exceptions. Some have been restored to mint condition, others have suffered from insensitive additions and improvements, but every one of these 11th and 12th century buildings can tell us a bit about the last phase of Byzantine Athens. Take the Russian church on Philellinon Street, for example. Once part of a large convent, Agios Nikodimos was built in 1031, on the site of an earlier church which had been constructed over some Roman baths. It contains marble used in the Classical Lyceum along with a throne from the theater of Dionysos and its terracotta Cufic designs imitating Arabic script were probably the work of Arab craftsmen. But Turkish cannonballs severly damaged the church in 1827 and it was eventually bought by Tsar Nicholas I for the Russian community here. The Greek state sold it on the condition that restoration would follow the original plan, but somehow the architects failed to comply. Restoration efforts and sheer neglect have taken a much harsher toll on the Sotira tou Kottaki in its charming garden on Kydathinaion Street. A 12th century church on a 6th century foundation, it had fallen into such disrepair that it was used as a urinal in the last century. So the cheap broken glass in the dome and unsightly window bars are in fact a step up. Here you see the characteristic Athenian dome, which is taller than in Byzantine churches elsewhere and has slim pillars framing each of its arches.

The next church is Agios Nikolaos Rangavas on Prytaniou Street. The most amusing way to reach it is by walking up Epimenidou, down Thespidos and then left onto Rangava, a mere path just under the Acropolis past a lovely garden. The church is by far the largest of the city's Byzantine jewels and dates from the same era as the monastery at Daphni, Kapnikarea and Agia Eleftheria next to the Metropolis, although a good percentage of it consists of later additions. Ancient blocks and columns are clearly visible next to the typically Byzantine brick decoration around the windows. This was the first church in Athens to acquire a belltower after the War of Independence (bells were forbidden in Ottoman territory) and the first to ring freedom in 1944. Now, if you go down Tripodon to Adrianou, Plaka's main shopping street, peek through the decrepit door at number 96 for a glimpse of the graceful arches fronting the Ottoman era house belonging to the Benizelos family. Given that St. Philothei was one of its members, you would think the Ministry of Culture would be more interested in restoring this elegant property. Inside the Agora, Agii Apostoli is the only church that has survived of the nine that once stood here. It was spared the wrecker's ball because of its distance from the heart of the Agora and its exceptional beauty. Outside the dome is supported on a typically Athenian high drum, inside it rests on ancient capitals, as does the altar. The narthex or vestibule contains plans and paintings showing the history of this thousand-year old church. Kapnikarea, an island in the middle of Emmou Street, is a familiar landmark. Look closely and you'll see the original 11th century building dedicated to the Virgin Mother received an addition in the 12th century: the chapel of St. Barbara, which is heavier and less graceful. Five different versions exist to explain the origin/meaning of its name. The word kapnos (tobacco or smoke) suggests it may have had something to do with a tobacco officials or an icon that survived fire and smoke. Some scholars think the name derives from kamouha, a valuable fabric made in the district, but no one will ever know for sure. Inside, there are frescoes done by Fotis Kontoglou in the 1950s, some beautifully carved modern church furniture, and some 19th century, Western-style paintings. These sentimental bland works predate a decision taken in the 1930s to have only two-dimensional traditional Byzantine-style icons and frescoes in Greek churches. After Kapnikarea's synthesis of pointed eaves and rounded arches, the "Small Metropolis" in the shadow of the Cathedral seems plain, but only from a distance. Instead of the traditional Byzantine brickwork, its walls are marble, decorated with a stunning collection of plaques from earlier buildings. An ancient Greek frieze depicts a calendar of Attic festivals and zodiac signs; below it flat, stylized pairs of birds and winged lions of Eastern origin are placed alongside a medieval cross being saluted by a Classical figure. Whoever assembled this amalgam of past art must have had great respect for its creators. The church was initially dedicated to the Virgin Gorgoepikoos – she who grants requests quickly – but after independence it was renamed Agia Eleftheria, which literally means St. Freedom. Who said there was a dearth of information? I've barely skimmed the surface and haven't even mentioned Agi Asomati at the bottom of Emou or Agi Theodon near Klathmonos Square. But Agios Ioannis on the corner of Evripdou and Koumoundourou streets beyond the Central Market deserves at least a line. This was a rural chapel and Ai Yannis had inherited the healing powers of Asklepios. Not much is left of the original structure except a Corinthian column rising above its makeshift roof. In the Middle Ages, the sick used to tie ribbons to it, hoping the saint would cure them, apparently, some people still do. The past, in all its manifestations, is always present in Greece, but the Byzantine era stopped short in Athens in 1205 after Western Catholic Crusaders parceled out the empire. That year, when the Franks severed Greece from its roots, can be considered the beginning of the real Dark Ages. As a former bishop exiled to Kea wrote, "You cannot look at Athens without tears." |

|