|

|

||||

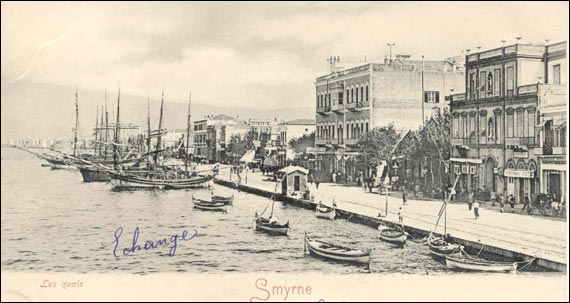

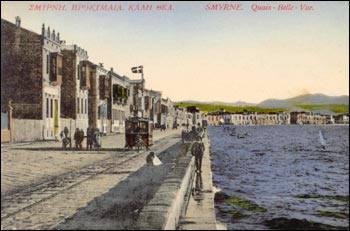

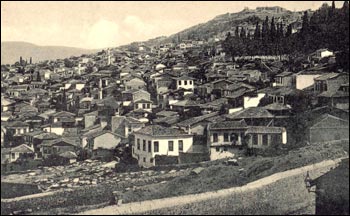

Since we have come to know this era through our parents' and grandparents' recounting as a nightmarish tale, we owe to the people who perished to offer them the appropriate commemorative honor and at the same time to allow their memory to become a positive component in facilitating our national identity. It is therefore appropriate to memorialize the sad events of that era that have become especially familiar in our island. Asia Minor was the natural site of expansion of Greek culture and since ancient times the Greek civilization flourished in that area. During the very early times a close association developed with mainland Greece and the Greek islands, thus creating a unified cultural region. In that area the Greek spirit, civilization and culture thrived for 3000 years. The island of Lesvos enters the Adramytti Bay crossways, with Ancient Troy located directly across from it. The island was historically and culturally associated with the seashores (the seashores of the Lesbian people, as they were known) of Ionia. Therefore we must search for Lesvos' cultural centers in the hub of the Hellenic Asia Minor, especially in Constantinople and Smyrna, and not in the metropolitan areas of mainland Greece. During the last years of the Turkish occupation and up to the day of the catastrophe, the Greek element -- regardless of the prosecutions, slaughters and forced Islamization that it had endured -- gained commercial and agricultural supremacy in the area. The cultural and academic element was very lively in Asia Minor, as they had established various organizations. Publications of books, newspapers and periodicals were part of their everyday existence. Throughout Asia Minor in Pontos and Eastern Thrace there were 2,150 flourishing Greek communities, thus proving that Hellas had conquered the occupant for the

After the first persecution, which lasted about three years, the Asia Minor exiles of Lesvos went back to their native lands. They longed to return to their familiar places, to their homes, to cultivate their land, to take care of their vineyards. They overcame the pain of their first forced exile and they found happiness again in their own terrain. The rich and productive Ionic and Aeolic earth was rewarding them and the rich produce of the East filled their homes and enriched their lives. Life was joyous! And they were still reliving moments of national pride. Since the Truce of Moudros in 1918, they experienced very touching historical moments, such as the landing of the Greek army in Smyrna and its endless victories and advances toward Sangarios River. Those were moments of high exaltation for them, but fate turned the tables around and their happiness transformed into misery. The uneasiness of the last months turned into anxiety, which transformed into panic. Kemal Ataturk and his Young Turk army were marching throughout the land devastating and wiping out all Christians and Hellenes. The Hellenic army in Asia Minor lowered its banners and the military trumpets played the song of rushed retreat. The nightmarish news was traveling from village to village and it was spreading terror. Most of the Greek population was running toward the ocean to be saved. Mothers grabbed their babies in their embrace and men clutched tightly the icons from their homes. They locked their homes and their prosperous stores, they draped in crude boxes their fears and hopes and miserably piled themselves in whatever old vessel they could find to get away from the place of disaster and calamity. The blue ocean was swaying their pain and their heartache back and forth and the August sea breeze was taking their lamentations back and mixed it with the cries of revenge from the crowd that was left behind. In the seashores of Panagiouda and Madamados they were endlessly crying under the August moon for the land they had left behind, the people that they might not ever see again, their properties, their very heart. These people however, were the lucky ones. What could one say about those that felt the cutting edge of the steel blade against their throat, for the girls who were raped, for the captives who suffered a slow death due to dire hardships at the hands of the Turkish menace!

Generally speaking, however, it is historically known that throughout Greece the waves of the unfortunate refugees caused distrust and fear that they would disturb the social balance of the Nation. The Asia Minor Catastrophe, without a doubt, caused a lot of hardship in contemporary Greece. There are words in the Greek vocabulary, such as catastrophe, turmoil, expulsion, uprooting that took on a special meaning during that era. The memory of the meaning behind these words is deeply rooted within us. Proud peoples bent down to their knees lamented and cried in the ashes of a luminous civilization that had been built with forethought and patience for thousands of years. Eighty years have gone by, but the wounds are still open. Whenever we look at photos that depict the Catastrophe, whenever we see Smyrna engulfed in flames we relive the painful moments again. Sad sensations sweep over us when we think what we had and what we lost. Today, when we visit Ionia and we see its endless fields and its continuous seashores and we know that these places were Hellenic and now they are not, the pain is really unbearable. Smyrna's Catastrophe was followed by the compulsory exchange of populations between Hellas and Turkey. This can be labeled as the final blow that the Hellenes of Asia Minor, Pontos and Eastern Thrace had to endure. If we could have avoided the exchange of populations during that time, the wounds would have been healed sooner, just as had happened with the first expulsion. This measure of compulsory expatriation that had been adopted by our "allies" was inhuman and violated the human rights of a certain group of people. No one has the right to transfer a whole group of people from their natural and social environment without their consent. Nationalities might have their differences, but they can coexist without intrusive governments who spread hate and fanaticism among people. The measure was harshly criticized by civilized nations. Even the Turkish Government's representative in the Lausanne meeting did not try to offer any excuses when the issue was discussed. The refugees that arrived in Vatousa, unlike other areas of the island, were not numerous. This is due to the fact that the Vatousan Asia Minor population stayed in Constantinople, where the Hellenic people were exempted from the exchange of population that took place in other places. On the other hand Vatousa was a poor and barren area, and not a region that would attract refugees to seek work. Nevertheless the refugees who came in Vatousa were enough to convey the extent of the tragedy. In the beginning the refugees of Vatousa weren't willing to believe that everything was lost, that from now on this place would be home for them. They thought that it was only a temporary nightmare and as soon as they will woke up they would be in their beautiful homeland -- in Fokies or Pergamon, Smyrna or Adramyti, Aivali or Dikeli. Their homes would be there, waiting for them and the fragrance of the basil plant would rush into the room as soon as they opened the windows. Dreams and fruitless hopes, and as time went on they were forced to accept the bitter reality that they were here to stay. They wiped the tears away, they gathered their strength and bit by bit they began rebuilding a new life. They worked hard, especially in the tobacco industry. Very soon they stopped being an encumbrance on the government budget and they began to contribute to the national economy. They did prove to the native Greeks that they were not the wretched, miserable lots who came to be a liability to them. On the contrary they proved that they had much to give through their work ethics. It is true, that not only the Vatousan refugees, but the Smyrna refugees throughout the Greek peninsula became instrumental in restoring the national homogeneity of the country, they replaced the Ottomans and they facilitated in the country's economic growth. They also exhibited their sensitivity developing collective relationships and they proved they had endurance and an ability to adjust. These were the values they had cultivated while they lived as a minority in a politically Ottoman environment. Their contribution to the cultural and economic development of contemporary Greece is really priceless. Very few of the ones who arrived as refugees in Hellas are still alive. They however, still carry with them the anguish and pain of their generation. They are the survivors of a group who dreamed a lot, but experienced very little and whatever they experienced most of it was bitterness. For most of the survivors now it is quite sufficient that they see their children and grandchildren breathing and living in a more peaceful environment. Asia Minor, Pontos and Eastern Thrace will forever be in our hearts. They are our lost homelands and we always carry them with us. Alas, if we were to forget them! Furthermore this bitter memory should not become an obstacle in our efforts to always strive ahead, to promote success. The end result of this harsh experience is that Hellas survived and progressed, even without the "Holy" lands that we lost. Therefore, let the commemoration of this experience become a cause not for tears any more, but for serious and productive thought. |

||||

|

|