SMYRNA COMMEMORATIVE SERIES |

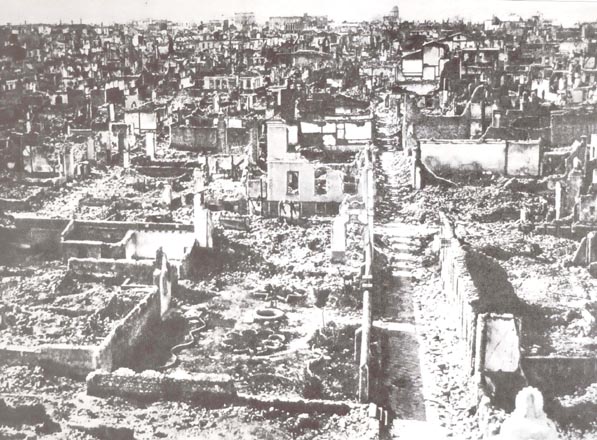

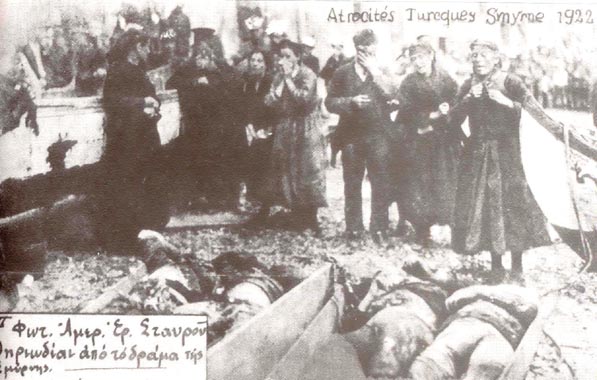

The English and French warships pour scalding water on swimmers approaching to climb aboard Now the life of our father was in danger, because they were gathering up the men. My father was 46 years old, and the age group which had been designated for capture was from 18-45. He appeared much younger, like a young bachelor. So, he had to do something to avoid being caught. We descended again to the wharf and saw the various war and merchant ships--English, American, French, and Italian--anchored at a distance from the shore. Our father says to us, "My children, I have to flee, because, if they catch me, I know I won't live. You, my daughter, you look like an old lady, and you, my son, are a young boy. So, they won't harm you. If they put you in a boat to send you from here, tell them that you want to go to Rhodes, because you have family there." He hugged and kissed us with bitter tears, and immediately pushed into the middle of the throng at the shore. Then he plunged into the water, and swimming, went to the French warship Ernest Renan. When he neared, he shouted to the officers and sailors, who saw him from the deck, and begged them to take him aboard. But they, hardhearted, motioned and shouted for him to leave. Grabbing the chains of the anchor, he persisted and begged. They answered by throwing boiling water down on him. The poor man, embittered, turned to head back. The distance was great, and being very tired, he almost drowned. Nevertheless, he succeeded in reaching the shore, and cried when he saw us. He hugged us and we cried together. Because he was soaking wet, my sister went to the wharf to search through the heaps of possessions for some clothes, so that he could change. She found a bundle of women's clothes and immediately thought to disguise him in women's garments. She brought them back and dressed him in along dress, stuffed a hump on his back, and covered his entire head, except his eyes, with a kerchief, and gave him women's shoes. So, we tried to take heart and went to sit near the destroyed buildings of the wharf, almost across from the "Doussou at bania" [Jardin de Bains near the Point?] There we met another man dressed as a woman who sat on the bare ground together with his wife and small children. He told us how he had tried yesterday to swim near the other French warship, the Waldeck Rousseau, and how the sailors had thrown boiling water down on him to make him leave. Lost on land, drowned at sea My father and my sister, who were both disguised as old women to hide their age and gender, sat down on the ground in a corner and didn't move from their places. But I, a 12-year-old boy, went around among the ruins out of curiosity. I went to the French Embassy, the marble-hewn building, on the pier. It was the only building in that area that, together with the Italian girls' school, they didn't burn. Next to the embassy was that magnificent building, the Theatre of Smyrna. It was burned and gutted. In the middle of the charred heaps were many burned corpses. These poor Romioi, they had gone in to hide, to flee the plunder and slaughter, with the hope that, because the building was attached to the French Embassy, the Turks would not set fire to it. Because the Turks saw many there, they shut them up inside and set fire to the building to burn them. What a horrible tragedy it was that has been recounted by people who saw it burn with their own eyes! From the Bella-Vista [Bella Vista Street] up to the customhouse, in one area of the wharf more than 2 kilometers in length, all the great centers, buildings, hotels, and rich mansions had burned. Indeed, the fire had destroyed the very foundation of the city, the entire sector in which were the Romiot quarters of Smyrna and the business center. Along the whole length of the shore, the sea was filled with drowned bodies. Everywhere in front of the Bella-Vista section there were so many drowned bodies, that, if you were to fall into the sea, you would not sink, because so many corpses would buoy you up in the ocean spray. You could see each corpse's swelled belly curving above the water. Some of these bodies were of people who, reaching the shore, were forced or thrown into the water by the pushing of the crowded masses. These masses had left their burning houses and run and thronged together at the shore to leave the hell of the fire. The water was deep here, too, more than 2 meters. But the floating corpses weren't just of these people whom the shoving had forced into the sea. There were those, too, whom the enemy, seeing them alive or seeing them dead—it was all the same to them—threw them into the sea with hatred. And there were those who had fallen into the sea to escape the blade of the enemy. Some girls were pushed into the sea by their parents, just as the enemy had come to seize them.  From the drowned bodies they took whatever of value was on them From the drowned bodies they took whatever of value was on themThese lifeless bodies were of men, women, and children. Of course, all Romioi. . . . And I saw about a dozen Turkish youth who were swimming among those entwined carcasses to take whatever of value they had on them. I stood and watched. They had covered their noses with kerchiefs tied behind their heads so as not to smell the rotten stench of the carcasses. They carried with them pointed knives and, with a great display, cut off the corpses' fingers that had rings and the tips of ears with earrings to take the jewelry. They grabbed bracelets and whatever valuables were also hidden in throats. They even thrust their hands into the women's cavities where there was nothing hidden. As for the male corpses, they thrust their hands into the pockets of the waistcoats to find a watch with a fob (as was the custom among the Smyrniots), into the pockets of the jackets and trousers, for a wallet, for money, or for anything else of value. They were so greedy that they took off shoes from the corpses, suspecting that when the dead people were still alive, they had hidden in them something valuable. And more—with their pointed knives they tried to take out the corpses' teeth that had golden crowns and bridges. Everything that they stole, they thrust into sacks tied to their waists. Prisoners gather the drowned bodies in the sea On Wednesday, the 7th (20th) of September 1922, we saw 25 prisoners naked and shoeless, with only a sack rolled up in the middle, prisoners who were wielding long poles with hooks at the tips. Enemy solders had brought them to the shore to gather the tangled corpses and to carry them off with carts so that they could bury them. Their stench had become unbearable. From the beach, they extended their poles, hooked each entwined corpse and dragged it through the water, bringing it near the wharf and lifting it out of the water. It was harsh and difficult work. The poor prisoners, although they weren't capable, were made to carry out the order, because the tips of the Turkish bayonets flashed near their naked torsos. They all toiled silently, apart from one person who was ill. A soldier saw that he couldn't manage it. He didn't quarrel with him, but stabbed and killed him and threw him into the sea. So, he drowned, too. Basic ignorance of an old Turk Together with all these things that we saw with our own eyes, I have to tell you about one other incident. As soon as the Turkish army entered Smyrna, a cavalry regiment arrived, with transport following it. When the transports stopped at the quay, we saw an old Turk, sitting atop one of the carts and gazing at the sea with curiosity. Hurriedly he got down from the cart and went near the water's edge where there were two small steps that led down to the surface. He appeared to be thirsty and descended the stairs. Stooping, he scooped up the saltwater in his palm and drank. But a cough seized him and he made choking sounds. He climbed the stairs enraged and ran toward the scant crowd of Romioi who stood in front of the quay. Then, he raised his two hands, cursed and blasphemed the Infidels "because they had thrown salt into the sea and made its water salty." The wretched old Turk had to have been from the very heart of Anatolia. It seems that this was the first time that he had seen the ocean. In his hometown he surely would have bent to drink water from some stream which certainly had fresh water. So, he was thinking that the sea also had sweet water and went to drink it. Its saltiness nevertheless shook him and his narrow-mindedness and his fanaticism made him suspect that the Giaour [Turkish term for Christians--literally "Infidel"] had salted it out of hatred.  They boarded the boat and were saved Tuesday the 13th (26th) of September 1922 dawned, the eve of the Elevation of the Cross. My father and I, dressed as women, and my sister, like a hideous old crone, sat on the pavement of the quay, near the Pouda [Point] where the boats come alongside and where they take the homeless and persecuted Romioi to wait. After eight hours, we saw a boat come alongside at the harbor of the Pouda. All the people who had been waiting to embark, ran straightaway to the harbor where there was a checkpoint. The Turkish soldiers were striking people with the butts of their rifles so that they would spread out and pass through in a line. We three, each one glued to the other, advanced with the crowd. When we reached the checkpoint, they let us three pass and board the boat. My father, because of his anxiety and pounding heart, lest they recognize that he was a man, started to faint. Once we boarded the boat, he fell to the deck unconscious. The boat cast off full of people. In the afternoon we reached Mytilene. The same evening two boats left from there for Smyrna to bring other people. Page 1 2 3 |

|

|