|

||

|

Galaxidi: A Port in a Time Warp |

||

|

This listed settlement of the mainland, which nevertheless resembles an island village, still bears echoes of its 19th-century shipping tradition By Diana Farr Louis |

A tiny section of what used to be an 8m-high wall that| encircled the town |

|

Galaxidi, in the Phokida prefecture, is that rare place in Greece which has not sold its soul to developers or tour operators. There is a photo in one of my albums of the port, Agora, taken thirty years ago. In classic gradations of black and white, its domed church, well-built houses and the vacant lot where a fragment of ancient wall runs through a tangle of daisies are reflected in a placid sea. Two weeks ago, I snapped the same image - in colour this time - and not a thing has altered. From a distance, that is. |

||

| On closer inspection, there are differences: more tavernas and cafes, fresh coats of paint on walls and woodwork, an atmosphere of subdued prosperity rather than hapless abandonment. But nothing that jangles: no plastic or neon, no maisonettes or souvenir shops. Galaxidi is in the process of reinventing itself, yet again. The Galaxidi that we see today is an echo of a 19th-century shipping emporium. This was but the latest manifestation of a town that kept being reborn on the same spot for well over 2,000 years. The pattern of settling, prospering and being plundered happened so often that it should have been called Phoenix. |

Called Agora by the locals, the port hasn't changed in appearance for at least 30 years |

|

| From prosperity to ruins and back Its ancient name was Chaleion, which is first heard of in the 4th century BC. At least two millennia before that the hills behind the peninsula bristled with small settlements, but even then their inhabitants were seafarers. Obsidian from Milos lay among their bones and pottery shards, while a round, flat-based amphora from those days turned up offshore in one of the earliest wrecks ever found. Eventually, their descendants moved down from the hills to the coast, where a string of deep coves offered protection to their ships. For extra insurance against pirate raids, however, they erected an 8m-high wall around the area above the two main coves. Some much diminished segments of this still exist, a few recycled as the foundations for 19th-century houses. |

||

| Chaleion's walls may have made it one of the safest ports in the Hellenic world, but they were no match for the tsunamis of mostly Slav tribes from the north who finished off the moribund Greco-Roman civilisation in central Greece. Compounded by an earthquake in the 6th century, their raids left the town deserted for three hundred years. When people finally felt secure enough to live on the coast again, they gave this place the intriguing name of Galaxidi, which translates as milk/vinegar - an incompatible match. It seems no such meaning was intended. No one knows for sure, but the word may commemorate a Byzantine leader, Galaxeides, who brought peace back to the region - for a while. Or it might refer to a local plant (galatsides). |

Hirolakas, Galaxidi's slightly wider second harbour |

|

The next several hundred years of history are variations on the same theme. A chronicle compiled by a monk named Efthymios in 1703 describes a repetitious but hardly monotonous cycle of "returning to... a pile of old ruins and stones.., rebuild[ing] houses and ships... because the sea had always provided their living" only to suffer "successive misadventures" with infidels, Franks and the Knights of St John, before succumbing to the Ottomans in 1446, followed by more pirate attacks and more earthquakes. But these people were nothing if not stubborn, and they seemed to thrive on adversity. In the early 18th century, Galaxidi started acquiring a major fleet, and thanks to the relaxation of Ottoman rules, their captains were allowed to arm themselves against the ever-menacing pirates. By the time the Greek War of Independence in 1821 broke out, Galaxidi ranked fourth after Hydra, Spetses and Psara in maritime strength. And like those islands, it offered its ships to form the navy. For this effrontery, the Turks devastated the town not once but three times. After the war, Galaxidi took off. From about 1830 to 1910, this little blip on the Corinthian Gulf was, improbably, the second most important port in Greece after Ermoupoli on Syros. In its heyday, Galaxidi's shipbuilders were turning out 15 to 20 sailing ships a year; their captains were carrying cargoes from Swansea to the Black Sea, all over the Mediterranean and across the Atlantic. With their considerable profits, they built sturdy, aristocratic houses that were far more comfortable than those of the shepherds and farmers in the hinterland. There were times when those houses looked out on a bay so full of sails, the water was barely visible. A piece of history To get an idea of the excitement of those years, don't miss the Nautical Historical Museum in a side street near the town church. It will introduce you to the Galaxiotes' love affair with the sea, through models, equipment, charts and figureheads, which were painted black when a captain died. Above all, the museum is a portrait gallery. Successful businessmen often commission portraits of what they value highest - themselves, their wives, their children, or even their racehorses, but these rooms hold no evidence of human relationships. Instead there are portraits of ships - stunning portraits done in meticulous detail by professionals as devoted to their subjects as their owners. |

||

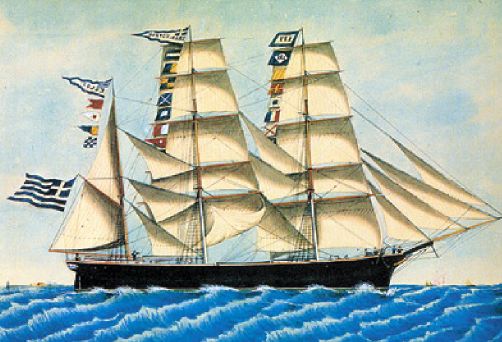

They fall into two categories: 19th-century 'life studies' by foreign artists, including three generations of Venetians, when the ships were abroad, and 20th-century nostalgia works by Greeks painting from their imagination. Among these are several poignant shipwrecks. It is the largest such collection in Greece. The museum charts the history of Chaleion/Galaxidi from before the Bronze Age to the 20th century. It ends with a few portraits of black, smoke-puffing vessels that bankrupted its 63 shipping agencies and mothballed its 500 sailing ships with extraordinary rapidity. |

The sailing ship 'Aiolos' is pictured in this watercolour by Vincenzo Luzzo displayed at the Nautical and Historical Museum of Galaxidi |

|

| Besides being more efficient, steamships were much more expensive to build and run. Galaxidi's fiercely independent sea captains could not bring themselves to form the partnerships required to make the transition from sail to steam. Every Greek knows that "only Chiots walk two by two"; trusting your neighbour does not come easily in this country. Thus began Galaxidi's decline. Some seafarers left for other ports, others reduced their horizons and took to fishing. By the 1920s, a local doctor/mayor invited his patients to donate memorabilia from the illustrious past for a museum. The Town Hall absorbed this new function, crowding it under its roof, which already housed the police station, a girls' elementary school and a carpet-weaving workshop. But the museum would not open its doors until 1962. After the war and civil war, Galaxidi was a ghost town in as desperate a state as it had ever been, without even a road to connect it to Itea, much less to the rest of the country. Then and now In my unorthodox and undoubtedly limited view, credit for resurrecting Galaxidi belongs to two very different groups of dedicated people. First, a strong-minded woman misnamed Zoe Tzingouni, which translates as 'stingy', wheedled a road out of the authorities in Athens and led the team which gained the museum the funds and legal papers it needed to survive. Successive dynamic curators and generous people kept it afloat, despite setbacks that threatened to damage the exhibits. Today, after a massive renovation paid for by the Niarchos Foundation, the museum has joined Greece's impressive list of beautiful small museums. But a place needs more than its past to be viable and here help arrived from a most unlikely source. In 1966, Bill and Bruno, an Australian/Italian gay couple, opened a small hotel in a former captain's house in a street behind the main harbour. Its nearest neighbour, rather incongruously, happened to be the School for Virgins (Parthenogogeio), an imposing edifice fronted by mock Doric columns. With their characteristic cheeky humour, the pair christened their hotel Ganimede (named after one of Zeus' male lovers) and furnished it with antiques, period paintings and, what struck me most of all, chic blue sheets. |

||

By the time I moved to Greece in the early 1970s, Bill and Bruno were famous in Athens. The Ganimede was reason alone to spend a weekend in Galaxidi. Old-timers will need no reminding that the term 'boutique hotel' had not yet been coined and that your average rural lodging in this country was a hymn to discomfort, cold, squalor and abysmal plumbing. Based on friends' rave reviews, we spent our first winter weekend at the Ganimede in |

This old wood carving likely belonged to the 'Aiolos', the biggest sailing ship to come out of Galaxidi's shipyards |

|

|

the late 70s. Bill was a fabulous cook, and Bruno was already serving the sort of breakfast that was unheard of in those days, with fresh orange juice and homemade jams. A few years later Bill died, and Bruno carried on. His Bergamo charm and those breakfasts became legendary, and we went back again and again just to bask in his hospitality.

In those early days, Galaxidi was pretty, atmospheric and dilapidated. Peeling paint, boarded-up windows, luxuriant weeds, sagging roofs saddened the eye on waterfront strolls. There wasn't much going on either. The best taverna was run by two octogenarians who produced the tastiest lambchops we've ever eaten in a dimly lit room with a dirt floor. Another old photo in our album shows a pot-bellied gentleman snoring on a tilted chair in the main street, his wide-brimmed hat covering his face like a cartoon Mexican. You don't see that any more. A string of bakeries lines that street, each offering mouth-watering Galaxidi sweets and delicacies (lihoudies). Cafes and tavernas have taken over almost all the buildings on the waterfront, especially on the smaller main port. Half-full on a Tuesday in April, they overflow at weekends and in summer (despite the heat). The few 'tourist' shops contain the work of local craftspeople, but their customers include locals. Many a restored captain's house sports a charmingly painted ceramic tile with the owner's name and a sailing ship next to the doorbell. Two of the cafes are art galleries and yet the town has resisted becoming twee. Bruno finally retired in 2003, but the Ganimede continues in the same hospitable tradition (with superlative jams) under Chrisoula and Costas Papalexis, aided by welcoming Nancy (Antanaska) from Bulgaria. Several more attractive hotels have followed Ganimede's lead, but although the temptation must be great to expand and go commercial, this is not likely to happen. First of all, Galaxidi is a listed settlement and, second, its residents seem to recognise that their heritage is their most valuable asset. As the mayor wrote in his prologue to the museum catalogue, "Our nautical tradition... will once more open new horizons for development and new prospects for Galaxidi. Only this time, it will not lead our citizens to the ends of the earth, instead it will... act as a magnet for visitors... leading them to learn to love our town... and be charmed by its uniqueness." How to get there Although there are plenty of hotels, try to get a room at Ganimede (-41328, www.ganimede.gr), or Hotel Galaxa (-41620, -41625, www.greek-tourism.gr/galaxidi/galaxa-hotel). Both are converted 19th-century captain's houses and serve lovely breakfasts - Ganimede in a charming courtyard, Galaxa on a terrace overlooking Hirolakas, the larger of Galaxidi's two harbours. Ganimede's rooms have period furniture; Galaxa's are island-style, spare blue and white. Ganimede was recently renovated and the bathrooms overhauled Photos by Diana Farr Louis |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 19 June 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||