|

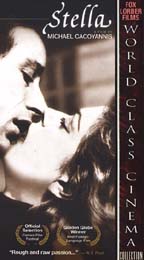

Representations of the Feminine in the Greek Crossover Films of Michael Cacoyannis and Jules Dassin

Page 1 2 3 4 Not coincidentally, the national identities of the directors of the three films mentioned above are put into question in the only book published in English on the history of Greek cinema, Mel Schuster's The Contemporary Greek Cinema (1979). Border-conscious Greeks have noted that the world's image of modern Greece is largely

Michael Cacoyannis has made many films about Greece, both classical and modern, including: Electra (1961), The Trojan Women (1971) and Iphigeneia (1977). His film Zorba the Greek, an adaptation of the novel The Life and Times of Alexis Zorbas by Nikos Kazantzakis, stars Anthony Quinn as the larger-than-life character of Zorbas. The international film community responded to Quinn's portrayal of Zorba, whose peasant wisdom and vitality, honed by hard experience, weans his timid employer, a half-Greek Englishman, away from his books and abstractions to find joy on the island of Crete. The film was nominated for seven American Academy awards, including a Best Actor nomination for Quinn, and four British Academy Awards. Quinn was born in Mexico, and his ethnic look contributed to his authenticity as a Greek character. In fact, Quinn seems to have cornered the market on playing ethnic characters in his films. He has appeared in other films as an Arab, a Filipino guerilla, an Italian-American, an Indian, a Native American, a Hawaiian, a Frenchman, a Spaniard, a Roman, and even an Eskimo, in 1959's The Savage Innocents. (IMDB.com) What this says is that audiences, trained by Hollywood to see the ethnic other as marked by difference, are willing to construct Quinn's characters in just about any role where the narrative binaries of the West are in place. In Cacoyannis' film, Zorba is the quintessential ethnic representative. While the Englishman is concerned with books, business, and the serious nature of life, Zorba is presented as fun-loving, uneducated, and taking pleasure in the physical aspects of life, such as drinking, dancing, singing, and sex. Zorba is a proud nationalist, whose war scars (only on the front of his body) tell the story of his place as the film's heroic, yet good-hearted villager. His famous lines spoken to the Englishman are, "I got hands, feet, head, they do the jobs, who the hell am I to choose? " ... " You think too much, that is your trouble, clever people and grocers they weigh everything" . . . "In work you are my man, but in things like playing and singing. I am my own" ... It is this mind/body split that forms the basis of the narrative, where the Greek character is valued for his flirtatious, un-thinking nature. In reality, we know this image is at odds with the many hard-working, intellectual, and successful Greek men and women immigrants throughout the diaspora. Roderick Beaton says of the story, "Kazantzakis exploits a traditional Greek background for purposes that transcend it." (Beaton, 177) Beaton even compares the novel to Plato's Republic, and insists that it succeeds because it "weaves together elements of the literary, philosophical, religious, and popular traditions of the Greek language since ancient times" (Beaton, 178). Beaton and others use a universalizing assumption about the value of literature, without considering the text's other minority, the female characters. When considering the film as a Platonic dialogue between the opposing forces of male/female, and East/West, another, less life-affirming meaning emerges. Both female characters in the film are narrowly defined classical archetypes of the tragic widow. Madame Hortence is an older, sentimental figure who is a sexual spinster. Zorba jokes that she has "killed off" her many lovers. Her melancholy state revolves around the fact that she is without a man. When Zorba enters her life and promises to marry her, Madame Hortence is given hope that she will once again be happy. Like Penelope, she waits for Zorba to return from his journey abroad, where he has since taken up with another woman named Lola. The promise of marriage is so important to her, however, that she would rather believe in the false hope of his love than face a life without a husband. She follows all of the stereotypes about women described above, as set forth by classical depictions of women. The myth persists that without men, women are unhappy to the point of not wanting to live. Even though Madame Hortence is a woman with her own historical importance (she is compared to Bouboulina for her efforts in stopping the war,) without Zorba, she admits that she would rather die. During this conversation, she is relegated to the space of the boudoir, and she is constantly associated with a decaying sexuality in the baroque mise-en-scene surrounding her. An allusion to Lysistrata is also present in her monologue about her involvement with war, "I stopped the boom-boom and got nothing, no medals." In love and war, Madame Hortence's subjectivity goes unrecognized by her male counterparts. The other tragic figure in the film is the young widow, played by actress Irene Papas. She is described as "a big, beautiful, wild widow," with whom many of the villagers are in love. Her sexuality is marked by her beauty, and reinforced by the fact that she is desired by the Englishman, who represents the marker of good taste and value. Most of the village harbors a hostility towards her, however, because her prized sexuality is guarded -- "They all want her and they hate her because they cannot have her." She spits in the eye of her most ardent admirer, Antoni's son, and ultimately meets her death when she consummates the relationship with the Englishman and is found out by the village. After she is called a whore, her house is stoned by the crowd, and she is stabbed by Antoni, the only person to come to her aid and lament is the village idiot. He is the only other character to empathize with the young widow, and is aptly someone who is separate from the patriarchcal norm; the only other character who is "not-man." Throughout the film, women are marginalized and made "other" by their difference from men, and alliance with all things aberrant because of their threatening sexuality. In the case of Hortence, the implication is that she is suffocatingly needy of sex. With the nameless young widow, she is marred by death and the absence of a husband -- a flaw deserving of violent punishment when she decides to act on her own accord sexually, with the Englishman. |

|