|

Virginia Kimball

"Drawn to the nourishing ark of sanctification": Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557) Special collection to remain on view until July 4, 2004

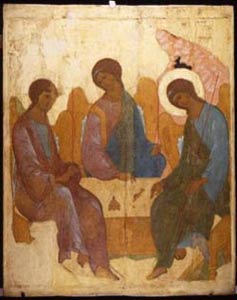

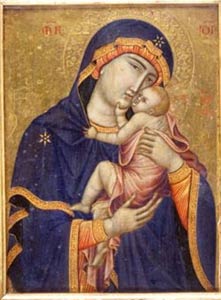

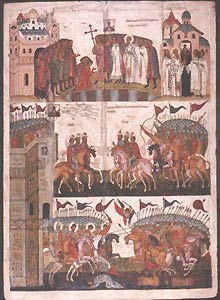

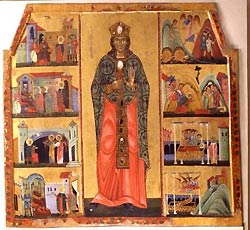

Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261-1557) opened at the Museum on March 23, 2004, third in a series displaying Byzantine iconography which began in 1977. The first exhibit, Age of Spirituality, focused on the third through the eighth century, followed in 1997 by Glory of Byzantium, AD 843-1261. This current exhibit focuses solely on the great artistic flowering of the Palaiologan period and "the subsequent appropriation of this culture by rival claimants to power," according to Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Museum. The current exhibit closes on July 4, 2004. It is not to be missed and for the world at large it is an invitation to the spiritual world. "Icons in their purest form are a way to contemplate the divine," according to Helen C. Evans, curator of the exhibition. Art here is a contemplation probing the reality of mystery – the incarnation of Christ, the holy face not painted with human hands, the life’s events of his mother, the Theotokos (Bearer of God), the saints, and Christ’s own life and miracles.

The Museum curators have attempted to communicate the exhibit in its context, "all of these becoming even an ark of Thy sanctification," as His Eminence Archbishop Damianos of Sinai described it all awhen he consecrated the exhibit. He suggested that such beauty embraces something more: God’s "impalpable becoming [is] approachable by us, and circumscribable in icons and varied works of art … made manifest for the common rejoicing and study." From room to room in the exhibit one passes from category to category rather than looking through sequential time. Paradoxically, the first room presents not only the empirical orientation of the ruling Palaiologi kings, but the nod these rulers made to the greater kingdom not of this world. Portable icons were carried high and proudly, usually acknowledging the protection of Christ’s mother. In this same room, we see a portable icon that was carried in

In the second gallery room, light is found in the darkness -- imagined in the fortress-like Byzantine architecture. It is a 13th century choros, a suspended lamp of cast copper alloy that held lighted candles, highlighted by silhouetted metalwork in patterned crosses, animals, and schematic designs. The piece demonstrates how Christian culture intersected with local symbol and image. Moving to the third room, one finds exquisite illuminated manuscripts including a canon table from a 13th century evangelion. Also, there is a promise to come in a 14th century fresco of St. Catherine and an unknown saint – a work that associates well with the room of art displayed from the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine on Mt. Sinai found later in the exhibit. In fact, St. Catherine is discovered in many rooms throughout the collection.

Also, many museum goers appeared fascinated in the fourth gallery room with displays of an epitaphios – a ritual object familiar to the eastern Christians but unusual in the eye of the public. This is a woven cloth of Christ’s crucified body, used in procession on Holy Friday in eastern liturgical use. The tradition is demonstrated by an especially appealing 14th century epitaphios from the Great Meteoran Monastery showing the particular Palaiologan era gold embroidery technique, especially in its field of stars surrounded by celestial beings and emblems of the four evangelists. Again, the catalogue selected this piece as "one of the most important liturgical objects of the treasury of this monastery," and here it is for all to see. In the fifth gallery room, more remarkable and elegant needlework of this period can be seen in vestments borrowing "power" in image from the royal leadership and yet carried out with the detailed eye and hand of ordinary people, the craftsmen. It reveals the same idea of mystery passing before the public’s eye and inviting transcendence. An actual photograph in the collection’s catalogue shows a contemporary procession at Mt. Sinai which reveals the majestic liturgical textiles in the vestments and epitaphios that is carried, pointing to an ebullience is that is humbly an invitation to the glory of Christ’s kingdom.

Entering gallery room seven subtly suggests entry to the monastery at Sinai itself. Museum planners constructed simple white rafters above to suggest the monastic environment, with a mere suggestion of an icon screen on the opposing wall suggesting the home for these Sinai items. For some, this is the most exciting gallery room in the exhibit. Rather than venture up the craggy precipices of Mt. Sinai, the glory of Sinai’s icons are here to see and still treasured in the exhibit’s catalogue. In a 13th century icon of Angel Gabriel, with the characteristic Palaiologian swirled gold halo, we find the one item that was chosen to represent the entire collection. Its form, say the scholars, is reminiscent of an earlier period but its technique speaks of 13th century hand. Its stylistic appeal draws in even contemporary eyes to the beauty of heavenly aspirations. A 14th century hexaptych with the traditional 12 panels representing the Great Feasts appears to be perhaps a portable icon but is placed in its usual position on the iconostasis above the Royal Gates – recalling the pivotal events of Christ’s life and the mother who bore him. It rolls salvation before the eyes: Christ’s incarnation, life on earth, death, resurrection and ascension, and finally the promise for all humans seen in the death of his mother when he takes her to Heaven.

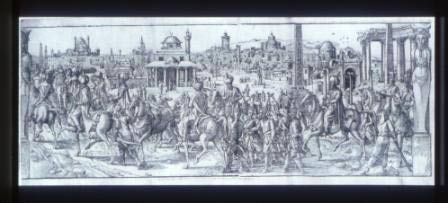

In Gallery room nine, the transition is made to Italy where Mendicant religious orders (specifically founded by St. Francis and St. Dominic in the 13th century) embrace the spiritual beauty of iconography in Byzantine tradition. The exhibit’s catalogue tells us: "Early in their history, mendicants realized the power of visual images to advance their mission (Anne Derbes and Amy Neff, "Italy, the Mendicant Orders, and the Byzantine Sphere," p. 449)." The orders, even after the founders were gone, continued the use of iconographic style to teach and inspire. The exhibit tours the visitor to Byzantium’s final influence on European art and religious décor. Room ten offers a succinct course in art history as it began in Europe and reached magnificence in Renaissance art, embracing still many of the secrets of earlier Byzantine craft. Perhaps most tantalizing will be the image of the Holy Face, the mysterious image of the "Face not made by human hands" which some trace to the very onset of iconographic practice – where the icon is more than a human depiction and in reality a window to the spiritual domain, a revelation of the divine.

The days are coming to a close for viewing this exhibit at the Metropolitan which closes July 4, 2004. Many of the individual pieces will reappear in other galleries and exhibits around the world. However, the best way to save the faith and power of this particular collection is to visit immediately the Metropolitan website www.metropolitanmuseum.org and then if so inclined to purchase the magnificent exhibit catalogue, Byzantium, Faith and Power (1261 – 1557), edited by Helen C. Evans, and published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Yale University Press, New Haven and London (ordering information found on the Museum’s website). The exhibition is made possible by Alpha Bank. Sponsorship was provided by The J.F. Costopoulos Foundation, the A.G. Leventis Foundation, and the Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation. Additional support was given by the National Endowment for the Arts and an indemnity was granted by the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. |

|