|

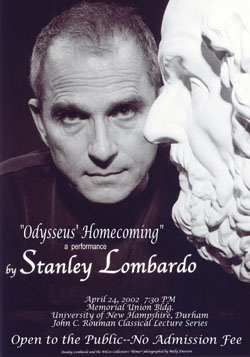

Odysseus' Homecoming

STANLEY LOMBARDO

JOHN ROUMAN CLASSICAL SERIES

UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

APRIL 24, 2002

Introduction by Mary Papoutsy:

Thank you, Dr. Hoskin. I won't keep you long. We have a wonderful evening scheduled.

I would like to introduce the principal performer tonight, a very distinguished person, an outstanding scholar, someone we have become acquainted with over the last couple of days, and I can also say a very fine person indeed.

Dr. Stanley Lombardo, so you will know a little bit about his background, is a professor of Classics at the University of Kansas and a native of New Orleans. He has done his graduate work at Tulane University and the University of Texas. In 1976 he joined the faculty at the University of Kansas, where he now teaches Greek and Latin at all levels as well as courses on Classical Mythology, Translation Theory and Practice, and Greek Literature and Culture. He has received a Kemper Teaching Fellowship and a Mortar Board award in recognition of his teaching.

His publications and his recognition for his scholarly work are innumerable, but we would like to single out a few of them for you, mostly literary translations of Greek poetry including Homer's Iliad. He has been a recipient of the Byron Caldwell Book Award. His translations have been performed by the Aquila Theatre Company at Lincoln Center. He has translated Homer's Odyssey; Hesiod’s Work and Days and Theogony, which has received a National Translation Center Award; Callimachus' Hymns, Epigrams and Selected Fragments, Aratus' Phaenomena, and Parmenides and Empedocles: The Fragments in Verse Translation. He has also published translations of Plato's Protagoras and Lysis and a selection of Horace's Odes in Latin Lyric and Elegiac Poetry. He also maintains an interest in Greek astronomy on which he has published two articles and taught several courses.

We are also bringing him here this evening not simply because of his wonderful scholarly background, but he is also a performer - a very noted performer. He has given dramatic readings of his translations on campuses throughout the country, as well as such venues as the Smithsonian Institution and the Chicago Poetry Center.

He has also been recorded and broadcast on National Public Radio, and we have seen him on CSPAN too. Some of you may have seen his appearance there a couple of years ago with Christopher Hitchens and a few other notables.

He is interested in Asian philosophy and has co-authored a translation of the Tao Te Ching. He has received transmission as a Zen master in the Kwan Um School of Zen and teaches at the Kansas Zen Center.

He is—was--currently working on a translation of Sappho's poems. But, we find out this evening it has just been published and has now been released. So, we look forward to reading that as well as his many other wonderful translations.

I am not going to delay any further; I would like to introduce Dr. Stanley Lombardo. He will be performing several selections of the Odyssey for you tonight and he will be accompanied by several musicians, my husband, Chris Papoutsy, on what looks like the dulcimer and we will call the “santouri” for this evening. He will be also be accompanied by a well-known violinist, Mr. Frederick Elias, who has given performances around the world. He has given even command performances for Middle Eastern royalty. So, we would like to welcome our principal performer and our guest this evening, Dr. Stanley Lombardo.

Dr. Stanley Lombardo

While the musicians are setting up I would like to take this opportunity to express my gratitude to having been invited to deliver the John C. Rouman lecture. Professor Rouman deserves to be recognized and honored for his contributions to preserving and transmitting classical culture for over one academic generation.

I would like to express my gratitude, of course, to Christos and Mary Papoutsy and recognize their foresight, imagination, and generosity in establishing this lecture.

I would like to express my gratitude to all three of these individuals for allowing me to dispense with the lecture and instead to transmit some of Homer's poetry the best way we know how-- through performance and music.

What we will be doing is in three parts. First, very briefly, an invocation to the Muse, that is, to the goddess who is our memory of this tradition, our memory of song and music. So, I will do that in Greek, Homeric Greek, and then two pieces from the main part of the Odyssey. The first half of Book Five of the Odyssey, if some of you would like to follow along, although it is not necessary. This is where Odysseus first actually appears in the poem. The first four books he is an absent figure. He is being sought for by his son, Telemachos. We know that he is being held captive on the island of Ogygia, owned by that nymph, Calypso, against his will. But the Gods have decided that it is time for that patient man to get to go home, and so he and Calypso have a memorable encounter in which he expresses his yearning to return to his home, to return to Penelope.

Then after Odysseus goes to sleep--goes to bed with Calypso for the last time--we move to the end of the Homeric poem. Odysseus has by this time come home. But he is not recognized--he is in disguise. He is recognized by his dog, who immediately dies—his faithful hound—and by his son, Telemachos. Odysseus and Telemachos weep when they embrace. He is recognized by the old nurse, Eurycleia, and makes her shut up. He reveals himself to three faithful servants. He is not recognized by Penelope, although there is some hint that their minds are getting closer on that subject. And he certainly is not recognized by the suitors, the one hundred and eight arrogant young men, who camp out at his house, drink his wine, eat his food and have their eyes on his wife. So, in other words, Odysseus is the typical veteran returning home after war to the usual situation.

So, we will go over that part. After Odysseus has killed the one hundred eight suitors and Penelope has been sleeping through all of that, as she sleeps through much of the poem, the two of them finally meet face to face and we see whose mind prevails at his homecoming--Odysseus who lives by his mind, or Penelope. Or is it really two minds coming together? So, maybe we can look for that. And afterwards, they will go to bed, finally. You know, it is sort of nice.

And after that, I think we will have on stage here members of the Advisory Board of Paideia. We will learn about that. There will be some people roaming the auditorium after my performance and we can have questions and discussions. So that is our satyr, our order of events for the evening.

ΟΔΥΣΣΕΙΑΣ Α

νδρα μοι έννεπε, Μούσα, πολύτροπον, ός μάλαπολλά

λάγχθη, επεί Τροίης ιερόν πτολίεθρονέπερσε•

ολλών δ’ ανθρώπων ίδεν άστεα καί νόον έγνω,

ολλά δ’ ό γ’ εν πόντω πάθεν άλγεα όν κατά θυμόν,

ρνύμενος ήν τε ψυχήν καί νόστον εταίρων. (5)

λλ’ ουδ’ ώς ετάρους ερρύσατο, ιέμενόςπερ•

υτών γάρ σφετέρησιν ατασθαλίησιν όλοντο,

ήπιοι, οί κατά βούς ΥπερίονοςΗελίοιο

σθιον• αυτάρ ο τοίσιν αφείλετο νόστιμον ήμαρ.

ών αμόθεν γε, θεά, θύγατερ Διός, ειπέ καί ημίν. (10)

Book Five, 1-

Dawn reluctantly

Dawn reluctantly

Left Tithonus in her rose-shadowed bed,

Then shook the morning into flakes of fire.

Light flooded the hall of Olympus

Where Zeus, high Lord of Thunder,

Sat with the other gods listening to Athena

Reel off the tale of Odysseus' woes.

It galled her that he was still in Calypso's cave:

"Zeus, my father--and all you blessed immortals—

Kings might as well no longer be gentle and kind

Or understand the correct order of things.

They might as well be tyrannical butchers

For all that any of Odysseus' people

Remember him, a godly king as kind as a father.

No, he's still languishing on that island, detained

Against his will by that nymph Calypso,

No way in the world for him to get back to his land.

His ships are all lost, he has no crew left

To transport him across the sea’s crawling back.

And now the islanders are plotting to kill his son

As he heads back home. He went for news of his father

To sandy Pylos and white-bricked Sparta."

Storm Cloud Zeus had an answer for her:

"Quite a little speech you’ve let slip through your teeth,

Daughter. But wasn't this exactly your plan

So that Odysseus would make them pay for it later?

You know how to get Telemachus

Back to Ithaca and out of harm’s way

With his mother's suitors sailing in a step behind."

Zeus turned then to his son Hermes and said:

"Hermes, my boy, you've been our messenger before.

Go tell that ringleted nymph it is my will

To let that patient man Odysseus go home.

Not with an escort, mind you, human or divine,

But on a rickety raft--tribulation at sea—

Until on the twentieth day he comes to Scheria

In the land of the Phaeacians, our distant relatives,

Who will treat Odysseus as if he were a god

And take him on a ship to his own native land

With donations of gold and bronze and clothing,

More than he ever would have taken back from Troy

Had he come home safely with his share of the loot.

That’s how he is destined to see his dear ones again

And return to his high-gabled Ithacan home."

Thus Zeus, and the quicksilver messenger

Laced on his feet the beautiful sandals,

Golden, immortal, that carry him over

Landscape and seascape on a puff of wind.

And he picked up the wand he uses to charm

Mortal eyes to sleep and make sleepers awake.

Holding this wand the tough quicksilver god

Pirouetted off Pieria

And dove through the ether down to the sea,

Skimming the waves like a cormorant,

The bird that patrols the saltwater billows

Hunting for fish, seaspume on its plumage,

Hermes flying low and planing the whitecaps.

When he finally arrived at the distant island

He stepped from the violet-tinctured sea

On to dry land and proceeded to the cavern

Where Calypso lived. She was at home.

A fire blazed on the hearth, and the smell

Of split cedar and arbor vitae burning

Spread like incense across the whole island.

She was seated inside, singing in a lovely voice

As she wove at her loom with a golden shuttle.

Around her cave the woodland was in bloom,

Alder and poplar and fragrant cypress.

Long-winged birds nested in the leaves,

Horned owls and larks and slender-throated shorebirds

That screeched like crows over the bright saltwater.

Tendrils of ivy curled around the cave’s mouth,

The glossy green vine clustered with berries.

Four separate springs flowed with clear water, criss-

Crossing channels as they meandered in through meadows

Lush with parsley and blossoming violets.

It was enough to make even a visiting god

Enraptured at the sight. Quicksilver Hermes

Took it all in, and then turned and entered

The vast cave.

Calypso knew him at sight.

Calypso knew him at sight.

The immortals have their ways of recognizing each other,

Even those whose homes are in outlying districts.

But Hermes didn't find the great hero inside.

Odysseus was sitting on the shore,

As ever those days, honing his heart's sorrow,

Staring out to sea with hollow, salt-rimmed eyes.

Calypso, sleek and haloed, questioned Hermes

Politely, as she seated him on a lacquered chair:

"My dear Hermes Golden Wand, to what do I owe

The honor of this unexpected visit? Tell me

What you want, and I’ll oblige you if I can."

The goddess spoke, and then set a table

With ambrosia and mixed a bowl of rosy nectar.

The quicksilver messenger ate and drank his fill,

And then settled back from dinner with heart content

And made the speech she was waiting for:

"You asked me, goddess to god, why I have come.

Well, I’ll tell you exactly why. Remember, you asked.

Zeus ordered me to come here; I didn't want to.

Who would want to cross this endless stretch

Of deserted sea? Not a single city in sight

Where you can get a decent sacrifice from men.

But you know how it is: Zeus has the aegis,

And none of us gods can oppose his will.

He says you have here the most woebegone hero

Of the whole lot who fought around Priam's city

For nine years, sacked it in the tenth, and started home.

But on the way back they offended Athena,

And she swamped them with hurricane winds and waves.

His entire crew was wiped out, and he

Drifted along until he washed up here.

Whatever. Zeus wants you to send him back home. Now.

The man's not fated to rot here far from his friends.

It's his destiny to see his dear ones again

And return to his high-gabled Ithacan home."

He finished, and the nymph's aura stiffened.

Words flew from her mouth like screaming hawks:

"You gods are the most jealous bastards in the universe—

Persecuting any goddess who ever takes

A mortal lover to her bed and sleeps with him.

When Dawn caressed Orion with her rosy fingers,

You celestial layabouts gave her nothing but trouble

Until Artemis finally shot him on Ortygia—

Gold-throned, holy, gentle-shafted assault goddess!

When Demeter followed her heart and unbound

Her hair for Iasion and made love to him

In a late-summer field, Zeus was there taking notes

And executed the man with a cobalt lightning blast.

And now you gods are after me for having a man.

Well, I was the one who saved his life, unprying him

From the spar he came floating here on, sole survivor

Of the wreck Zeus made of his streamlined ship,

Slivering it with lightning on the brandy-eyed sea.

I loved him, I took care of him, I even told him

I’d make him immortal and ageless all of his days.

But you said it Hermes: Zeus has the aegis

And none of us gods can oppose his will.

So all right, he can go, off on the sterile sea,

Done by order from above. How I don't know.

I don't have any oared ships or crewmen

To transport him across the sea’s broad back.

But I'll help him. I’ll do anything I can

To get him back safely to his own native land."

The quicksilver messenger had one last thing to say:

“We’ll send him off now and watch out for Zeus' temper.

Cross him and he might really be rough on you later."

With that the tough quicksilver god made his exit.

Calypso composed herself and went to Odysseus,

Zeus' message still ringing in her ears.

She found him sitting where the breakers rolled in.

His eyes were perpetually wet with tears now,

His life draining away in homesickness.

The nymph had long since ceased to please.

He still slept with her nights in her cavern,

An unwilling lover mated to her eager embrace.

Days he spent sitting on the rocks by the breakers,

Staring out to sea with hollow, salt-rimmed eyes.

Calypso stood close to him and started to speak:

"You poor man. You can stop grieving now

And pining away. I’m sending you home.

Look, here is a bronze axe. Cut some long timbers

And make yourself a raft fitted with topdecks,

Something that will get you across the sea's misty spaces.

I'll stock it with fresh water, food, red wine--

Hearty provisions that will stave off hunger–and

I’ll clothe you well and send you a following wind

To bring you home safely to your own native land,

If such is the will of the gods of high heaven,

Whose minds and powers are stronger then mine."

Odysseus' eyes shown with weariness. He stiffened,

And shot back at her words fletched like arrows:

"I don't know what kind of send-off you have in mind,

Goddess, telling me to cross all that open sea on a raft,

Painful, hard sailing. Some well-rigged vessels

Never make it across with a stiff wind from Zeus.

You're not going to catch me setting foot on any raft

Unless you agree to swear a solemn oath

That you're not planning some new trouble for me."

Calypso's smile was like, well like yours, but like a shower of light.

She touched him gently and teased him a little:

"Blasphemous, that's what you are--but nobody's fool!

How do you manage to say things like that?

All right. I swear by earth and heaven above

And the subterranean water of Styx--the greatest

Oath and most awesome a god can swear-–

That I'm not planning more trouble for you, Odysseus.

I'll put my mind to work for you as hard as I would

For myself, if ever I were in such a fix.

My heart is in the right place, Odysseus,

Nor is it a cold lump of iron in my breast."

With that the haloed goddess walked briskly away

And the man followed in the deity's footsteps.

The two forms, human and divine, came to the cave

And he sat down in a chair which moments before

Hermes had vacated, and the nymph set out for him

Food and drink such as mortal men eat.

She took a seat opposite godlike Odysseus

And a maid served her ambrosia and nectar.

They helped themselves to as much as they wanted,

And when they had their fill of food and drink

Calypso spoke, an immortal radiance upon her:

"Son of Laertes in the line of Zeus, my wily Odysseus,

Do you really want to go home to your beloved country

Right away? Now? Well, you still have my blessings.

But if you had any idea of all the pain

You are destined to suffer before getting home,

You’d stay here with me, deathless--

Think of it, Odysseus!--no matter how much

You missed your darling wife and wanted to see her again.

You spend all of your daylight hours mooning after her.

I don't mind saying she’s not my equal

In beauty, no matter how you measure it.

Mortal beauty cannot compare with immortal."

Odysseus, always thinking, answered her this way:

"Goddess and mistress, don't be angry with me.

I know very well that Penelope,

For all her virtues would pale beside you.

She’s only human, and you are a goddess,

Eternally young. Still, I want to go back.

My heart aches for the day I return to my home.

If some god hits me hard as I sail the deep purple,

I'll weather it like the sea-bitten salt that I am.

God knows I’ve suffered and had my share of sorrows

In war and at sea. I can take more if I have to."

The sun set on his words, and the shadows darkened.

They went to a room deep in the cave, where they made

Sweet love and lay side by side through the night.

Book Twenty-Three, 1-

The old woman laughed as she went upstairs

To tell her mistress that her husband was home.

She ran up the steps, lifting her knees high,

And, bending over Penelope, she said:

"Wake up, dear child, so you can see for yourself

What you have yearned for day in and day out.

Odysseus has come home, after all this time,

And has killed those men who tried to marry you

And who ravaged your house and bullied your son."

And Penelope, alert now and wary:

"Dear nurse, the gods have driven you crazy.

The gods can make even the wise mad,

Just as they often make the foolish wise.

Now they have wrecked your usually sound mind.

Why do you mock me and my sorrowful heart,

Waking me from sleep to tell me this nonsense--

And such a sweet sleep. It sealed my eyelids.

I haven't slept like that since Odysseus

Left for Ilion--that accursed city.

Now go back down to the hall.

If any of the others had told me this

And awakened me from sleep, I would have

Sent her back with something to be sorry about!

You can thank your old age for this at least."

And Eurycleia, the loyal nurse:

"I am not mocking you, child. Odysseus

Really is here. He's come home, just as I say.

He's the stranger they all insulted in the great hall.

Telemachus has known all along, but had

The self-control to hide his father's plans

Until Odysseus could pay the arrogant bastards back."

Penelope felt a sudden pang of joy. She leapt

From her bed and flung her arms around the old woman,

And with tears in her eyes, she said to her:

"Dear nurse, if it is true, if he really has

Come back to his house, tell me how

He laid his hands on the shameless suitors,

One man alone against all of that mob."

Eurycleia answered her:

"I didn't see and didn't ask. I only heard the groaning

Of men being killed. We women sat

In the far corner of our quarters, trembling,

With the good solid doors bolted shut

Until your son came from the hall to call me,

Telemachus. His father had sent him to call me.

And there he was, Odysseus, standing

In a sea of dead bodies, all piled

On top of each other on the hard-packed floor.

It would have warmed your heart to see him,

Spattered with blood and filth like a lion.

And now the bodies are all gathered together

At the gates, and he is purifying the house

With sulfur, and has built a great fire,

And has sent me to call you. Come with me now

So that both your hearts can be happy again.

You have suffered so much, but now

Your long desire has been fulfilled.

He has come himself, alive, to his own hearth,

And has found you and his son in his hall.

As for the suitors, who did him wrong,

He’s taken his revenge on every last man.”

And Penelope, always cautious:

"Dear nurse, don't gloat over them yet.

You know how welcome the sight of him

Would be to all of us, and especially to me

And to the son he and I bore. But this story

Can't be true, not the way you tell it.

One of the immortals must have killed the suitors,

Angry at their arrogance and evil deeds.

They respected no man, good or bad,

So their blind folly has killed them. But Odysseus

Is lost, lost to us here, and gone forever."

And Eurycleia, the faithful nurse:

"Child, how can you say this? Your husband

Is here at his own fireside, and yet you are sure

He will never come home! Always on guard!

But here's something else, clear proof:

The scar he got from the tusk of that boar.

I noticed it when I was washing his feet

And wanted to tell you, but he shrewdly clamped

His hand on my mouth and wouldn't let me speak.

Just come with me, and I will stake my life on it.

You can torture me to death, if I am lying to you."

Still wary, Penelope replied:

"Dear nurse, it is hard for you to comprehend

The ways of the eternal gods, wise as you are.

Still, let us go to my son, so that I may see

The suitors dead and the man who killed them."

And Penelope descended the stairs, her heart

In turmoil. Should she hold back and question

Her husband? Or should she go up to him,

Embrace him, and kiss his hands and head?

She entered the hall, crossing the stone threshold,

And sat opposite Odysseus, in the firelight

Beside the farther wall. He sat by a column,

Looking down, waiting to see if his incomparable wife

Would say anything to him when she saw him.

She sat a long time in silence, wondering.

She would look at his face and see her husband,

But then fail to know him in his dirty rags.

Telemachus couldn't take it any more:

"Mother, how can you be so hard,

And hold back like that? Why don't you sit

Next to father and talk to him, ask him something?

No other woman would have the heart

To stand off from her husband who has come back

After twenty hard years to his country and home.

But your heart is always colder than stone."

And Penelope, cautious as ever:

"My child, I am lost in wonder

And unable to speak or ask a question

Or look him in the eyes. If he really is

Odysseus come home, the two of us

Will be sure of each other, very sure.

There are secrets between us no one else knows."

And Odysseus, who had borne much, smiled,

And his words flew to his son on wings:

"Telemachus, let your mother test me

Here in our home. She will soon see more clearly.

Now, because I am dirty and wearing rags,

She is not ready to acknowledge who I am.

But you and I have to devise a plan.

When someone kills just one man,

Even a man who has few to avenge him,

He goes into exile, leaving country and kin.

Well, we have killed a city of young men,

The flower of Ithaca. Think about that."

And Telemachus, in his clear-headed way:

"You should think about it, Father. They say

No man alive can match you for cunning.

We’ll follow you for all we are worth,

And I don't think we’ll fail for lack of courage."

And Odysseus, the master strategist:

"Well, this is what I think we should do.

First, bathe yourselves and put on clean tunics

And tell the women to choose their clothes well.

And then have the singer pick up his lyre

And lead everyone in a lively dance tune,

Loud and clear. Anyone who hears the sound,

Passer-by or neighbor, will think it's a wedding,

And so word of the suitors’ killing won't spread

Down through the town before we can reach

Our woodland farm. Once there we'll see

What kind of luck the Olympian gives us."

They did as he said. The men bathed

And put on tunics, and the women dressed up.

The god-like singer, sweeping his hollow lyre,

Put a song in their hearts and made their feet move,

And the great hall resounded under the tread

Of men and silken-waisted women dancing.

And people outside would hear it and say:

"Well, someone has finally married the queen,

Fickle woman. Couldn't bear to keep the house

For her true husband until he came back."

But they had no idea how things actually stood.

Odysseus, meanwhile, was being bathed

By the housekeeper, Eurynome. She

Rubbed him with olive oil and threw about him

A beautiful cloak and tunic. And Athena

Shed beauty upon him, and made him look

Taller and more muscled, and made his hair

Tumble down his head like hyacinth flowers.

Imagine a craftsman overlaying silver

With pure gold. He has learned his art

From Pallas Athena and Lord Hephaestus,

And creates works of breathtaking beauty.

So Athena herself made his head and shoulders

Shimmer with grace. He came from the bath

Like a god, and sat down on the chair again

Opposite his wife, and spoke to her and said:

"What a mysterious woman.

The gods The gods

Have given to you more than to any

Other woman, an unyielding heart.

No other woman would be able to endure

Standing off from her husband, who has come back

After twenty hard years to his country and home.

Nurse, make up a bed for me so I can lie down

Alone, since her heart is a cold lump of iron."

And Penelope, cautious and wary:

"You're a mysterious man.

I’m not being proud

I’m not being proud

Or scornful, nor am I bewildered--not at all.

I know very well what you looked like

When you left Ithaca on your long-oared ship.

Nurse, bring the bed out from the master bedroom,

The bedstead he made himself, and spread it for him

With fleeces and blankets and silky coverlets."

She was testing her husband.

Odysseus, who had borne much, Odysseus, who had borne much,

Could bear no more, and he cried out to his wife:

"By God, woman, now you’ve cut deep.

Who moved my bed? It would be hard

For anyone, no matter how skilled, to move it.

A god could come down and move it easily,

But not a man alive, however young and strong,

Could ever pry it up. There’s something telling

About how that bed's built, and no one else

Built it but me.

There was an olive tree There was an olive tree

Growing on the building site, long-leaved and full,

Its trunk thick as a post. I built my bedroom

Around that tree, and when I had finished

The masonry walls and done the roofing

And set in the jointed, close-fitting doors,

I lopped off all of the olive's branches,

Trimmed the trunk from the root on up,

And rounded it and trued it with an adze until

I had myself a bedpost. I bored it through with an auger,

And starting from this I framed up the whole bed,

Inlaying it with gold and silver and ivory

And stretching across it oxhide thongs dyed purple.

So there's our secret. But I do not know, woman,

Whether my bed is still firmly in place, or if

Some other man has cut through the olive's trunk."

At this, Penelope finally let go.

Odysseus had shown he knew their old secret.

In tears, she ran straight to him, threw her arms

Around him, kissed his face, and said:

"Don't be angry with me, Odysseus. You,

Of all men, know how the world goes.

It is the gods who gave us sorrow, gods

Who begrudged us life together, enjoying

Our youth and arriving side by side

To the threshold of old age. Don't hold it against me

That when I first saw you I didn't welcome you

As I do now. My heart has been cold with fear

That an imposter would come and deceive me.

There are many who scheme for ill-gotten gains.

Not even Helen, daughter of Zeus,

Would have slept with a foreigner had she known

The Greeks would go to war to bring her back home.

It was a god who drove her to that dreadful act,

Or she never would have thought of doing what she did,

The horror that brought suffering to us as well.

But now, since you have confirmed the secret

Of our marriage bed, which no one has ever seen—

Only you and I and a single servant, Actor's daughter,

Whom my father gave me before I ever came here

And who kept the doors of our bridal chamber--

You have persuaded even my stubborn heart."

This brought tears from deep within him,

And as he wept he clung to his beloved wife.

Land is a welcome sight to men swimming

For their lives, after Poseidon has smashed their ship

In heavy seas. Only a few of them escape

And make it to shore. They come out

Of the grey water crusted with brine, glad

To be alive and set foot on dry land.

So welcome a sight was her husband to her.

She would not loosen her white arms from his neck,

And rose-fingered Dawn would have risen

On their weeping, had not Athena stepped in

And held back the long night at the end of its course

And stopped gold-stitched Dawn at Ocean's shores

From yoking the horses that bring light to men,

Lampus and Phaethon, the colts of Dawn.

Then Odysseus said to his wife:

"We have not yet come to the end of our trials.

There is still a long, hard task for me to complete,

As the spirit of Tiresias foretold to me

On the day I went down to the house of Hades

To ask him about my companions’ return

And my own. But come to bed now,

And we’ll close our eyes in the pleasure of sleep."

And Penelope calmly answered him,

"Your bed is ready for you whenever

You want it, now the gods have brought you

Home to your family and native land.

But since you’ve brought it up, tell me

About this trial. I’ll learn about it soon enough,

And it won't be any worse to hear it now."

And Odysseus, his mind teeming:

"You are a mystery to me. Why do you insist

I tell you now? Well, here's the whole story.

It's not a tale you will enjoy, and I have no joy

in telling it.

Tiresias told me that I must go

To city after city, carrying a broad-bladed oar,

Until I come to men who know nothing of the sea,

Who eat their food unsalted, and have never seen

Red-prowed ships or the oars that wing them along.

And he told me that I would know I had found them

When I met another traveler who thought

The oar I was carrying was a winnowing fan.

Then I must fix my oar in the earth

And offer sacrifice to Lord Poseidon,

A ram, a bull, and a boat in its prime.

Then at last I am to come home and offer

Grand sacrifice to the immortal gods

Who hold high heaven, to each in turn.

And death shall come to me from the sea,

As gentle as this touch, and take me off

When I am worn out in sleek old age,

With my people prosperous around me.

All this Tiresias said would come true."

Then Penelope, watching him, answered:

"If the gods are going to grant you happy old age,

There is hope your troubles will someday be over."

While they spoke to one another,

Eurynome and the nurse made the bed

By torchlight, spreading it with soft coverlets.

Then the old nurse went to her room to lie down,

And Eurynome, who kept the bedroom,

Led the couple to their bed, lighting the way.

When she had led them in, she withdrew,

And they went with joy to their bed

And to their rituals of old.

Telemachus and his men

Telemachus and his men

Stopped dancing, stopped the women's dance

And lay down to sleep in the shadowy halls.

After Odysseus and Penelope

Had made sweet love, they took turns

Telling stories to each other. She told him

All that she had to endure as the fair lady

In the palace, looking upon the loathsome throng

Of suitors, who used her as an excuse

To kill many cattle, whole flocks of sheep,

And to empty the cellar of much of its wine.

Odysseus told her of all of the suffering

He had brought upon others, and all of the pain

He endured himself. She loved listening to him

And did not fall asleep until he had told the whole tale.

He began with how he overcame the Cicones

And then came to the land of the Lotus-Eaters,

And all that the Cyclops did, and how he

Paid him back for eating his comrades.

Then how he came to Aeolus,

Who welcomed him and sent him on his way,

But since it was not his history to return home then,

The storm winds grabbed him and swept him off

Groaning deeply over the teeming saltwater.

Then how he came to the Laestrygonians,

Who destroyed his ships and all their crews,

Leaving him only with one black-tarred hull.

And then all of Circe's tricks and wiles,

And how he sailed to the dank house of Hades

To consult the spirit of Theban Tiresias

And saw his old comrades there

And his aged mother who had nursed him as a child.

Then how he heard the Sirens' eternal song

And came to the Clashing Rocks,

And dread Charybdis and Scylla,

Whom no man had ever escaped before.

Then how his crew killed the cattle of the Sun

And how Zeus, the high Lord of Thunder,

Slivered his ship with lightning, and all his men

Went down, and he alone survived.

And he told her how he came to Ogygia,

The island of the nymph Calypso,

Who kept him there in her scalloped caves,

Yearning for him to be her husband,

And how she took care of him, and promised

To make him immortal and ageless all his days

But did not persuade the heart in his breast.

Then how he crawled out of the sea in Phaeacia,

And how the Phaeacians honored him like a god

And sent him on a ship to his own native land

With gifts of bronze and clothing and gold.

He told the story all the way through,

And then sleep, which slackens our bodies,

Fell upon him and released him from care.

(Back row, left to right) Bill Gatzoulis, President of Paideia of New Hampshire; Penelope Salmons; Dino Siotis, Director of the Press Office of the Consulate General of Greece in Boston and Editor of MondoGreco literary magazine; (front row, left to right) Christos and Mary Papoutsy, series benefactors and members of the advisory board; Dr. John C. Rouman, Professor Emeritus of the Classics Department of the University of New Hampshire; Dr. Stanley Lombardo, guest performer and lecturer; Prof. Nina Gatzoulis of the Modern Greek Program of the University of New Hampshire.

|