|

||

|

Monk-ey Business on Skyros |

||

|

An island that has hung onto its traditions and shunned large-scale tourism faces the prospect of being overrun by alternative energy By Jonathan Carr |

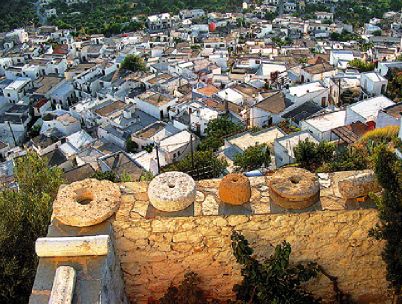

A panoramic view of the Hora from the monastery of Agios Georgios |

|

| Venetians, Turks and plenty of pirates including Barbarossa, the worst of them all, who sacked the place in 1538. Today, there may be a military presence on Skyros but it is discreet and nobody is expecting the island to have to stand alone if it were ever to come under fire. The occupation Skyros faces now is of a different, more insidious, kind. As we fly in over the island, from south to north, we get our first feel for the stunning dichotomy of the landscape. Almost equally split in terms of land mass, Skyros' two halves were most likely separate islands during some distant geological age. Today, a low-lying sandstone valley (just 4 kilometres across) unites the bare brown mountains of the south with the pine-forested slopes of the north. As we pass over those mountains and admire their bleak beauty we do not yet know that this land - home to the Equus caballus skyriano (the unique Skyrian horse) and some endangered plants as well as an important stopping-off point for migratory birds - could soon be home to a new genus that Homo sapiens is proposing to introduce. The magnificent Windus turbineus is an offshoot of the more solitary (and now mostly gentrified) Windmillus. The particular species that is being proposed for Skyros is said to reach an average height of 130 metres, weigh 300 tonnes and its 'wind' is audible - impressively - from half-a-kilometre away. Wind turbines quickly take over and drive out all indigenous creatures in a given area if introduced in sufficient numbers. Had a poor sailor called Athanassios never been dropped off here in AD960, the turbines might not pose the threat that they now do to the Skyrian way of life. Traditions |

||

Our taxi driver claims the island is very welcoming to visitors but they do not want "very rich ones". What he seems to be implying is that ostentation is frowned upon, and this is quickly borne out by the discreet nature of Skyros' new buildings. There is a welcome absence of big brash hotels and no evidence of any package tourism. Development, on the whole, is modest and sympathetic to the landscape. For anyone who has seen the vulgar villas that scar so many of the hillsides of Skyros' nearest neighbour, Alonnisos, this restraint is commendable. You can still find bays with not much more than the odd taverna on them. And even ones with small settlements, like the wooded bay at Atsitsa on the northwest coast where the UK-based Skyros Centre has for many years run New Age courses, retain their character and sense of quietude. |

A mixed group of Skyros ponies and mules that live in the wild near the grave of poet Rupert Brooke |

|

|

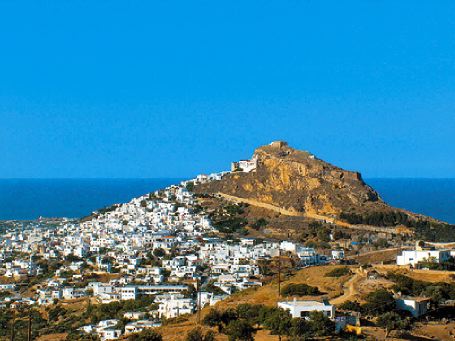

The first sight of the Hora brings a little convulsion to the spine. Like the best of its Cycladic cousins, it is gleaming white and half-way to heaven, elegantly riding a huge rock outcrop. On the very top are the remains of a mostly-Byzantine Kastro, while just below is a little ring of buildings formed by the monastery of Agios Georgios (which is playing, as we shall discover, a critical role in the probable introduction of the wind turbines). And next, in all its lucent dazzle, comes the town. Impressively, the web of alleys and steps and arches has been kept in a splendid state of preservation. Wandering around them as the sun sets and the air cools is as delightful now as it probably ever has been. The houses mostly retain the hand-carved furniture and decorations of more than a century ago - walls are lined with displays of porcelain and copper plates. These were collected obsessively in the past and denoted a family's status, the ownership of a 17th-century Delft plate from Holland, for example, being a great coup. There are ceramic vases, wooden utensils, textiles and glassware. Cloth is most commonly embroidered with cockerels (a sign of fertility) and boats (representing the course of a human life). And because the buildings are so small, floor space is carefully rationed and some of the furniture - chairs and tables - are child-size. Often, Hora residents are found perched on them in the shade outside their doorways. Old-style courtesy and curiosity persist. "Do you like our island?" they want to know. Give them the nod and they are genuinely delighted. |

||

|

More likely, though, Skyros is just that kind of island where - despite all the petty feuds that exist - most people are mostly happy most of the time. The maintenance of tradition depends on active and willing participation and one prime example of that, unique to Skyros, is the goat dance held each year during the carnival season. Its pagan origins are evident enough and - who knows? - perhaps its origin can be traced all the way back to the time of Troy. A parallel is certainly there. Dance groups usually consist of three characters - an old man (the yeros) who wears a goat mask, a hairy black coat like a goatskin and a large number of bells around his waist. He prances around the streets like a madman (albeit a cunning one) attended by a young man dressed up as a woman, also wearing a goat mask. He/she dances round the yeros and sings while a third character has fun representing a Frangos - a western European of the 17th century. |

The island's small port at Linaria |

|

|

It is the transvestite who may provide a link with the Homeric hero Achilles. His mother Thetis, a sea-goddess, knew that if he went to Troy he would achieve great fame but would not return alive. So she hid him on Skyros, in the palace of King Lykomedes, disguised as a girl. The secret of his whereabouts was betrayed and Odysseus arrived, aware that without Achilles the Greeks would never take Troy. What the wile Odysseus came up with this time was a little masterpiece. He arrived in the palace weighed down with gifts of jewellery and fabrics for the ladies of the court. But he also included one well-wrought sword and belt. The trumpet sounded. The women hurried over and threw themselves excitedly on the gifts and the great Achilles could not, of course, help revealing himself once he saw that gleaming blade. He stripped himself to the waist and buckled up. It must have been quite a moment. "Ah," Odysseus must have said, "Mr Achilles, I presume?" Or something like that. Another story that connects modern Skyros with Achilles is related by Nikos Kritikos, agricultural engineer at the Municipality as well as the president of the Skyros Horse Association. It was Skyrian horses, he says, that Achilles took to Troy and those same Skyrian horses are the ones you can see depicted on the Parthenon frieze. He produces pictures on his computer screen and reminds us that people, like the horses, were smaller in those days too. |

||

Smaller? Yes, the Equus caballus skyriano rarely stands higher than 1.1 metre. This kind of horse used to be all over the Aegean. But not any more. And they have only survived on Skyros, Nikos explains, because of the use to which they have been put. Until machines arrived in about 1970, the system was a perfect example of human/equine symbiosis. In the winter months, the horses were set loose on the southern mountains because there was water and good pasture, but in the summer months - between June and September - they needed the north's verdure. This was also the season when the islanders required the horses to crush and thresh their various grains - wheat, split peas etc. So they fed and watered the horses who, in a quid pro quo, would turn the threshing wheel, in groups of up to six at a time. With the season over, they were released again into the mountains. There were said to be about 1,000 of them on the island in those days. |

Gleaming white, the Hora graciously straddles a huge rock outcrop |

|

|

But once there was no longer any agricultural need for them they began to die off. In 2000, when Nikos carried out a count, there were only 85 left. Now, due to a mixture of hard work, volunteering, charitable donations, EU subsidies and government incentives to breed, that number has risen to 105 adult horses. A database giving details of them and their breeding pedigree is in a well-advanced state. Nikos shows us the details he has on the most successful stud (paternity is established through DNA testing). He is a good-looking chestnut-brown horse. His name is Hector. Hector? Nikos grins. Don't worry, there is an Achilles too, he says. We have high hopes for him. |

||

|

Brooke's association with Skyros may have been slight but the island could hardly be accused of having let his death be forgotten. Besides the evident care taken to keep his grave in good condition, back in Hora there is another memorial. On a promontory that commands views down to the shoreline of Magazia and Molos is a large pebbled circle in the centre of which stands a bronze statue "to Rupert Brooke and Immortal Poetry". A youth holds a parchment in his right hand, and his left looks as though it might once have held a quill. He is naked. The statue apparently caused some controversy when it was first erected, not least because some considered it to be indecent. Why a statue of a naked youth should prompt this kind of response in a country that pioneered them is a mystery. A far more pertinent question would be whether the statue looks incongruous in this particular setting. It does. |

Hand-carved furniture and decorations of more than a century ago make up a typical Skyrian house |

|

| Back at Brooke's grave near Tris Boukes, our brief reverie is interrupted by a soft snorting sound. We look up to discover, not far away among the trees, a small group of Skyrian horses (and some mules) gathered in the shade. We draw closer and watch them for a while. They, too, watch us. And, face to face with this endangered species, we work out that even if you stood the whole of today's population on top of each other, they would still not reach the height of a single wind turbine. Windus turbineus Poor sailor Athanassios was put ashore on the island in AD960 by his friend Emperor Nicephorus Phocas (according to islander Manos Faltaits, in his history book Skyros). Phocas promised to give Athanassios all the lands belonging to the Monastery of St George, should he return victorious from his forthcoming campaign on Crete. Phocas won, returned and kept his word. Athanassios later became a monk and founded the Megistis Lauras monastery on Mount Athos, to which - crucially for today's inhabitants - he transferred ownership of the land belonging to the Monastery of St George on Skyros. Athanassios was apparently pious and humble, a man of ethics and integrity. He was later made a saint. The proposed introduction of the Windus turbineus on Skyros, if it were to go ahead, would be the largest such introduction of the species anywhere in Europe. No matter that Skyros is only 24 kilometres long. The current plan sees them packed in. No less than 111 (each spanning about 80 metres) would be placed across much of the southern half of the island. It is estimated they could generate 330 megawatts of power, thereby fulfilling 10 percent of Greece's EU obligation for the generation of alternative energy by 2010. When they are first established in new terrain, there is enormous disruption - new roads, enlarged port facilities, lots of noise. They drive out other species and once their wheels start spinning, migratory birds get caught in them. Their introduction will mean the end of the Skyrian horse, whose habitat they will take over. I am no expert and we all know the world of alternative energy is fraught with arguments. One point, though, can be made with confidence. The scale of these proposals brings only one benefit, so dear to Homo sapiens - economic. The bigger the project, the lower the costs, the bigger the profits. And, doubtless, the islanders who support the project (opinions seem split - and fiercely so) are convinced they will share handsomely in these. But who would care most about the profits? Obviously, the owners of the company that would install and operate them. And who are these lucky folk? The owner of nearly all the land on which the 111 wind turbines would be installed is the Megistis Lauras monastery on Mount Athos. The proposals circulating envisage an operating company that would be 95 percent owned by the monastery, 5 percent by an outfit called Enteka AE. So, if this scheme goes ahead, the monks - counting pieces of silver at their pristine, untouchable base on Mount Athos - will demonstrate precisely why we should consider them paragons of our greedy species. What on earth would their founder have thought about their behaviour? Athanassios, after all, was said to be a man of ethics and integrity. |

||

How to get there Olympic Airlines has flights to/from Skyros on Wednesdays and Saturdays (cost around 35 euros). Otherwise, a ferry boat travels daily between Kymi, on the coast of Evia, and Skyros' port of Linaria Where to stay In the Hora, Efrosini Karabini (tel 22220-92319) has some rooms in traditional houses. There are no signs up, but others may approach you on your arrival in the main 'plateia'. A good beach alternative is the Hydroussa Hotel, Magazia (www.hydroussahotel.gr, tel 22220-91209) Where to eat 'O Pappous kai ego' in the Hora offers some outstanding Greek specialities, while down on the beach at Molos 'Kokallenia' is a delightful place which serves an excellent version of the local lobster-and-pasta dish 'astamakaronada' Photos by Jonathan Carr |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 23 August 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||