|

||

|

To the Grave of Nikos Kazantzakis

|

||

|

In the first of a two-part travel series Mark Sargent engages in a literary pilgrimage to Crete - from Arkadi monastery to Rethymno and Hania. Next week's issue takes us to Iraklio RUMBLE and roar of engines, stench of diesel, rattle of chain and clang of iron to iron, the last lorry creeps aboard. The ramp lifts and the Aptera is cast free. The pilot throttles up and we ease away. Cars flash and flow along the nighttime Piraeus waterfront, to the south something is burning. Kazantzakis opens Zorba on this waterfront, a rainy dawn, a cafe full of fishermen waiting out a storm. His narrator is brooding over |

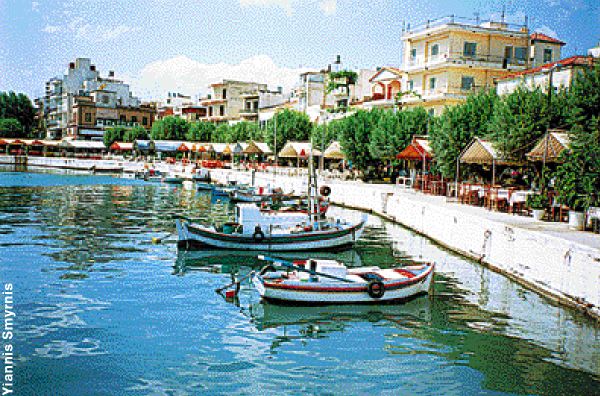

A classic view of Rethymno's harbour |

|

| missed opportunities, his life as an intellectual and his hope of finding redemption through opening a lignite mine in Crete. He then opens a copy of Dante but hesitates, unsure which verse would be appropriate to begin the day. He never decides, for at that moment he becomes aware of Zorba, staring at him through the window. It is August 31 and I'm off for my first visit to Crete; after more than 15 years in Greece, my first visit. I'm travelling with my companion Mirella, her 18-year-old son George and his friend Klara. We are bound for Rethymno, there to secure housing for George, who begins university there in October. We've allotted ourselves 10 days on the island, plenty of time to explore, to think about Crete and Kazantzakis and what the world has become in his absence. Earlier in the day, riding the electric train back to Piraeus from a Plaka lunch with my son, I got a quick glance of a dilapidated old house, the word CANCER painted large over the front-door lintel. Has cancer reached plague proportions in the city? Do they believe it's contagious? Or is it some manner of biblical Passover? Perhaps the angel of vengeance fears cancer and moves on, to the children of the as yet uninfected? Or does it mean he's already visited? It's a tired but ever demanding metaphor, this 'cellular condition', this auto-immune aberration that science keeps saying we have brought upon ourselves. The lights of Attica begin to dim, we churn on into the black Aegean. I have with me Kazantzakis' Report to Greco, a memoir; The Saviours of God, spiritual exercises; and The Odyssey, A Modern Sequel. I'm reading them simultaneously, leaping back and forth as my mood dictates. It is an exhilarating dance. |

||

What a tormented child he was, if we are to believe his memoir, which even the ever-faithful Helen Kazantzakis was moved to admit, veers at times into fictional excess. Yet she says we should judge him "not by what he did, and whether what he did was or was not of supreme value; but rather by what he wanted to do, and whether what he wanted to do had supreme value for him, and for us as well." Supreme value. Who even thinks in these terms in the early days of the 21st century, especially with regard to art? I ask the young, but quite literate, George, whether the great man holds the interest of young Greeks. Alas, no, his fervid nationalism and near-hysterical search for god and meaning seem religious and ancient to the new materialists. This was a man, after all, who, at the age of 25, free of all responsibility and footloose in Italy, fears |

The historic Arkadi monastery at the foothills of Mount Ida |

|

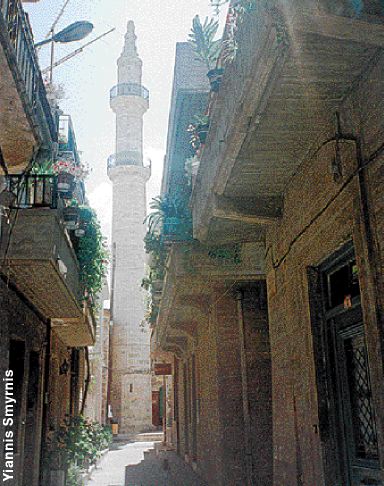

| he is enjoying himself too much, fears that special hubris and so, to reconnect with suffering, buys a too small pair of shoes and hobbles 'round Florence in agony. "How many times as I gazed at the beautiful bodies in Renaissance paintings, bodies so resplendent with seeming immortality, was I overcome by unbearable sorrow and indignation because all the divine forms which had been the pretext of those paintings had rotted away and returned to dust... beauty has always left an aftertaste of death on my lips." No wonder he was travelling alone. On the front page of the IHT is a picture of a man running across a flooded New Orleans street. The Aptera plunges south into the darkness. Newest of moons heralds the dawn, long strands of light mark the sleeping Rethymnon From the rooftop verandah of our old town inn, the lone surviving minaret of Rethymno, serene above the jumbled crap and concrete of modern Greece, is silent. There are no faithful any more, there is only commerce, the consumer and the consumed. It's okay, it will crumble as fast as us - what is left? Our knowledge of the human spirit, the song of it. |

||

"And listen: in sleep, in an act of love or creation, in a proud and disinterested act of yours, or in a profound despairing silence, you may suddenly hear the Cry and set forth." The Saviours of God. And nothing will ever be the same, and you will find rest only in the grave. On a back street away from the tourist shops we find a kafenio specialising in meze and raki. We go three nights in a row. The proprietor - large, bearded, with a laughing grace, epitome of the Cretan hero - has stepped out of a Kazantzakis novel to ply these streets with marides, dakos (a Cretan concoction of paximadi, cheese and tomato), roast goat and so on. From our |

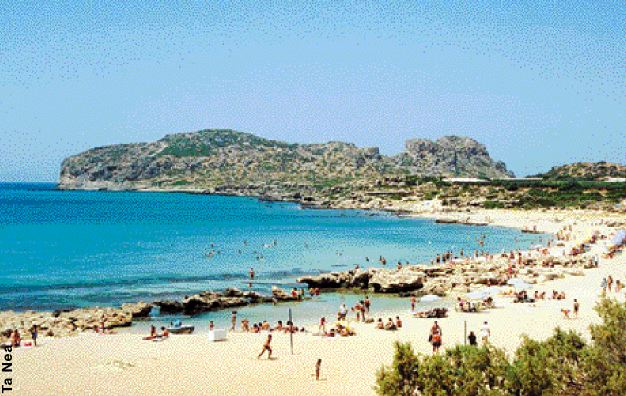

The beautiful beach of Falasarna in Hania |

|

| table in the narrow street we see everything. Strands of light strung across the street between the decaying three-storey Venetian buildings cast the alley in soft gold, there's just enough local foot traffic to entertain. Old men on classic motorcycles, teenage girls all done up, gangs of young men bumping against each other. We soon discover that our host owns the restaurant across the street and a shop next door. He floats between them. He knows everyone. What industry! And carried off with such panache. More raki? But of course, on the house. It is such a perfect delight that we will probably never find it again. Nights such as these vaporise at dawn and can never be recovered. "Women are simply ornaments for men, and more often a sickness and a necessity." Report to Greco. The heart and soul of traditional Crete speak. At the foothills of Mount Ida the historic Arkadi Monastery is being beautifully restored at great expense. The soft earth tones of the new plaster work give it a New Mexico Pueblo look, but the arches give it away, they didn't know the arch in the western hemisphere. Tacked to a long dead cypress, a white plastic cursor points to a lone Turkish bullet embedded just before the mass suicide by Cretan partisans. Their skulls are on display but all the rest is dirt. There seems to be some confusion over who actually lit the powder magazine. Was it the warrior Giamboudakis or the Abbot Gabriel who expressed them to heaven rather than face degradation at the hands of the loathsome Turk? But 114 did survive, were taken prisoner and, as predicted, endured humiliation and horrible conditions. But then, according to a text I purchased in the monastery museum, "having spent one year in prison, the prisoners were released and returned to their villages to continue the Cretan Revolution." Huh? That doesn't sound like a fate worse than death to me. I believe I'd take the year in the slam, I don't care how bad the food was. Now political suicide barely gets you on the front page. All martyrs are touched with madness. We miss the turnoff for Anoyia, but know the story anyway. After Paddy Fermor and the lads snatched the German General Kriepe in Iraklio, Anoyia was where they spent the first night. Its reward was to be burned to the ground and every male executed. Several months later the German army marched through the Amari valley doing village a day the same for one week; retribution, the Germans claimed. What was the strategic value of the General snatch? What could he have known about the German plans for the defence of Crete that in April of '44 would justify such risks? The Allies were in Italy and two months from the D-day invasions. Yet George Psychoundakis, in The Cretan Runner, claims that the German "reprisals" were actually a campaign to terrorise the population, especially the resistance, prior to the German withdrawal to Hania. Outside Crete, the kidnapping is now remembered mostly for Major Fermor and General Kriepe, upon Mount Ida, trading Latin verses of an Horatian ode as the first light of dawn spread over the Libyan Sea. "We had both drunk at the same fountains long ago," writes Fermor. In a revolutionary situation, perhaps they would have been on the same side? One imagines that if this operation had been purely Cretan, the general's throat would have been cut long before he reached the summit. Without a word of poetry. In old vaulted Venetian church in Hania I stare into the face of Tiberius, of Hadrian, and sure the artist made them handsome, heroic, cut from the pure stone of Rome. Capable of command, certainly. In a large glass display case are dozens, perhaps a hundred clay figures of bulls, from thumb to small-dog size. Wonderful, you can almost hear them bellow with desire. Why aren't there any small children with their faces pressed and steaming against the glass? I'm their stand-in, but don't, I can focus from here. |

||

I wade through the foreign press, awash with Hurricane Katrina. Why are we so willing to believe preliminary guest-i-mates made in the midst of disasters? And what is it about the figure 10,000? In Chinese poetry it is used to connote a vast, endless distance. In the States it rests just this side of hyperbole, anything more would be hysterical. It was a holy figure in the first days of 9/11 and those who questioned it were accused of belittling the fallen. In the shade of a pine tree, dripping the beautiful waters of Falasarna, I read out loud to George from The Saviours of God. "Love each man according to his contribution in the struggle. Do not seek friends; seek comrades-in-arms." Already a veteran of many demonstrations and well-versed in Marxist-Leninist theory, he perks up. "Klara, listen to this!" I repeat. They nod their heads. Ah, a small Comrade Kazantzakis worm has entered their minds. |

The lone surviving minaret in Rethymno's old town |

|

|

Geese paddle and honk along the Almiros River, the reed beds, bamboo and eucalyptus wave in the twilight, aged tourists shuffle out to find sustenance. The denizens of Georgioupolis put on their smiles and hail them with vigour. Kazantzakis never witnessed the despoliation of Crete. He had a greater vision. "A severe, unsilenceable responsibility weighs heavily on his shoulders, on the shoulders of every living Greek. The name itself possesses an invincible, magical force. Every person born in Greece has the duty to continue the eternal Greek legend." And turn every sleepy fishing village into a greedy uncontrolled pile of concrete, fried food and porcelain gewgaw. Rows of jolly little satyrs sporting stupendous erections compete with t-shirts and baubles for madam. And the mind-numbing, depressing part of it is not so much that it's crap, but that it is the same crap in town after town. Every hamlet on the sea is pitching a bust of Sophocles. It has been years since I've swum in fresh water and the sensation, when I shed my clothes and dive off the paddle boat into Lake Kournas, is one of weight. At first it feels like the water is heavy, then I realise it is me, without the benefit of salty buoyancy, sinking in the cool dark water. It is midday, alas, and all the vaunted wildlife, save the odd gull and goat, are resting in the dark. Read the second article of Sargen, "Unraveling Ariadne's Thread." |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 26 September 2006) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||