|

||

|

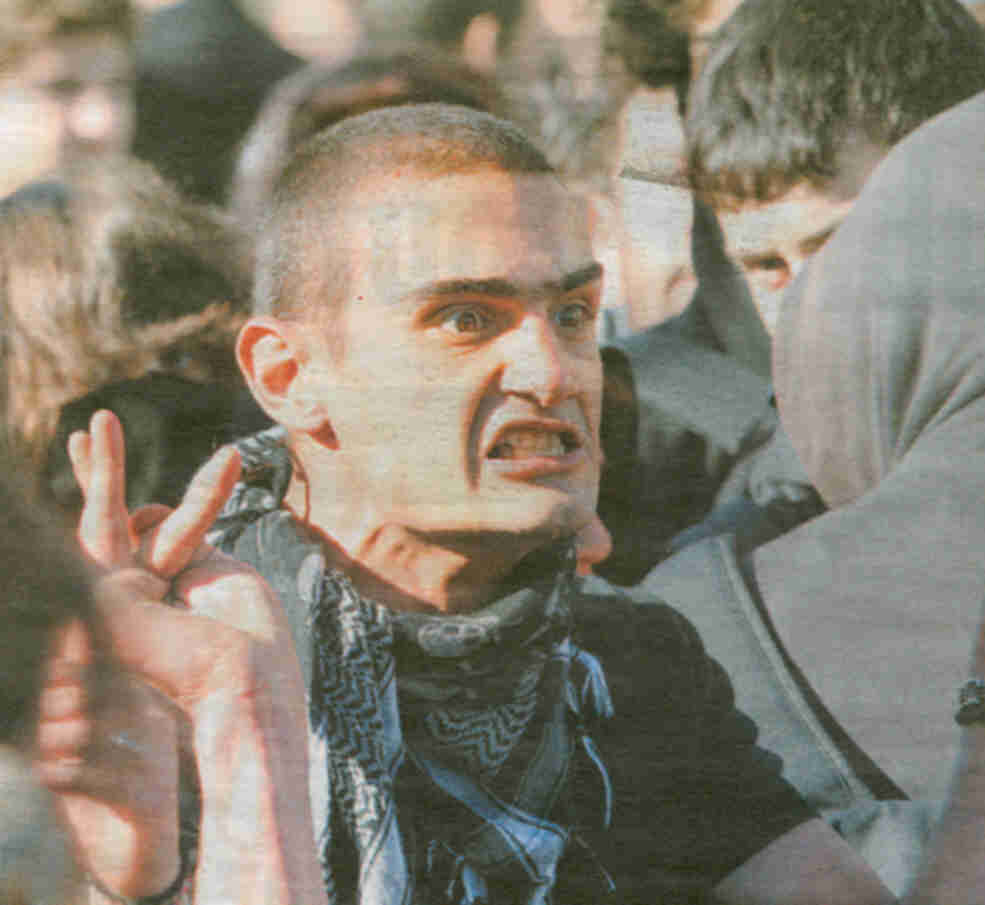

The Politicisation of Youth |

||

|

Editorial

By John Psaropoulos editor@athensnews.eu THE WEEK of rioting that followed the shooting death of a fifteen-year-old boy on December 6 took Greece, literally, by storm. Although the worst rioting was in Athens, sympathy riots spread to virtually every comer of Greece - the first time in recent political history that this has happened in such a widespread manner. How did things get so out of hand? Did the riots spontaneously spark a powder keg of dissatisfaction or were they cynically fanned by political forces? Were they hijacked by criminals or were they fuelled by teenagers' giddy sense of empowerment? |

||

Most likely, all four are true. That a few criminals might piggyback on general unrest should surprise noone. (Hurricane Katrina saw a marked rise in the New Orleans murder rate, already one of the city's most salient points, because some people saw it as the ideal scoresettling camouflage.) And the collegiate spirit that sweeps teenagers into group behaviour is barely resistible at the socialising stage in the life of any mammal. It is the deeper causes of dissatisfaction and the political manipulation of youth that ought to trouble the country most. Greece has been working against the interests of the younger generation for some time. Massive public debt, built up in the 1980s has never been paid down - on the contrary, it has risen. The young people rioting or merely demonstrating last week will pay with interest for the pension hikes that are now routinely promised at every election, because retirees are such a large voting bloc. They will also pay with interest for the early retirement given to about 500 professions including civil servants. The debate over last summer's pension reform revealed just how unwilling Greeks are to assume the costs one generation incurs within that generation. Labour minister Fani Palli Petralia was roundly criticised for daring to suggest that 35 years in the labour force were no longer enough to qualify for retirement if one had not reached the age of 65. And she was shouted out of a retirement threshold of 58 for workers with 37 years to their credit. Alekos Alavanos, who leads Syriza, the parliamentary bloc of Synaspismos, or Left Coalition, and professes a particular understanding of youth, then asked the president to reject the legislation. Yet he offered no counter -proposal to save social security from bankruptcy. Pasok has now made it an electoral promise to repeal the law. Just as animals are inadequately represented in the discussion of hunting laws, the young are underrepresented in the discussions of costs we plan to export to their future. Already the sum of all taxes raised from personal and corporate income this year, an estimated 12 billion euros, will go to the servicing of our increasingly expensive national debt. That leaves the government only the income from VAT, fuel tax and customs, propelling it into a vicious cycle of more borrowing. No party seems to have the guts to say that we need to spend less. The wastefulness of the Greek state doesn't stop at lack of pension reform; our columnist, Mark Dragoumis, has already discussed the absurdity of an average 11 percent rise in public sector costs since 2002 to reach 49.55 billion euros this year (see the Athens News edition of September 12). Civil servants are responsible for a chunk of that. Their numbers have grown by more than 55,000 under New Democracy to more than half a million, because Prime Minister Costas Karamanlis promised full tenure to 200,000-odd fixed-term employees on public payroll. The waste that accompanies public procurement also remains out of reach under what had billed itself as a transparent, reformist government that was going to 're-found' the state. Rather than cleaning house after the socialists, the conservatives seem to have made a menage a deux with them. Despite a string of financial scandals over four years, no one has been held accountable before the law. Where the conservatives have tried to legislate with a view to the long term, they have met with asphyxiating opposition. Hence the difficulty in breaking closed professions - the key to developing market size and jobs through innovation. Hence, also, the difficulty in selling off state behemoths and creating an investment environment for foreign capital. The worst opposition came with New Democracy's most ambitious undertaking over four years - to reform education. Pasok initially went along with a 2005 bill to introduce assessment for public universities, and initially supported a revision of article 16 of the constitution. That would have brought Greece into line with European law and prepared it to become part of a single higher education environment by 2010. The bipartisan train was derailed by Alavanos in 2006. Desperate for a cause to save his party from what seemed like certain extinction at the next general election, he seized upon education reform. Alavanos managed to mobilise anti-reformist university rectors and labour unionists who represent a minority of academics. Through the student unions Synaspismos maintains on campuses across the country, he enlisted a large army of student protesters. The rallies were impressive. Though they came short of what we have seen over the past week in terms of destructive spirit, they went on for months. In time, Alavanos was able to stir the jealousy at secondary school unionists who came with their pupils, swelling the street protests to the tens of thousands. Alavanos directed the student body to believe two things; that liberalisation of the university system did not merely allow regulated non-state enterprise but opened the door to a selling of the state system; thus he reshaped the debate as one of privatisation, which has been a Greek swearword since antiquity (idiotikopoiisi, to make private, gave English the word idiot); and he directed them to believe that then education minister Marietta Yannakou's attempt to depoliticise the university environment threatened to make the state a micromanager. The result of Alavanos' rabid war was that socialist leader George Papandreou lost his nerve. Facing a mutiny led by the more populist former culture minister Evangelos Venizelos, he reversed his support for liberalisation and became as outspoken as Alavanos against the Yannakou reform bill. Alavanos won his gambit. Synaspismos upped its share of the popular vote from 3.26 to 5.04 percent and increased its representation from 6 to 14 seats. Pasok fell, from 40.55 percent of the popular vote to 38.10, and from 117 seats to 102. Last week saw Alavanos leading Papandreou by the nose again. The self-appointed mouthpiece of youth gloated openly in television appearances over the December 6-7 weekend, relishing the opportunity to embarrass the government in the one arena he can - the street (see our interview with Alavanos on page 10). His deputy, Synaspismos leader Alexis Tsipras, was hardly better. Papandreou felt obliged to follow a shameless act of populism. As late as Monday he said that it was time for a government that couldn't face up to its responsibilities to resign, making no plea that might help quell the disturbances. Too late, Karamanlis, whose tactic during the early stages of a crisis is to, disappear (he did the same during the forest fires of August last year), asked party leaders to separate meetings on Tuesday. Even then Papandreou and Alavanos maintained their competitive defiance, calling for the government's resignation and early elections. Not until Wednesday did Papandreou call for restraint, well after most of the country had begun to hear for its livelihood, its physical integrity and its children. The media were complicit in this populism. They returned to a reflex reaction against law enforcement. Many major networks referred to the killing of Grigoropoulos as "the murder", seemingly unaware of the assumption. Only one network was chastened by the goings on, and it was that hosted by people in their teens and 20s. MAD television, the music video channel, showed its young presenters sitting cross-legged on studio couches taking phone calls from viewers about the riots. They looked drained of their usual effervescence and shell-shocked at how thin the fabric of order can be. Calling for a speedy return to order, they were perhaps the only indication that what the youth of Greece may want is not less authority but better authority; not total freedom but training in how to be free. It is not the province of this newspaper to comment on whether the mind of Alekos Alavanos is diabolically rational or sadly deranged in the pursuit of power; the question is ultimately immaterial; what matters is that his power to damage the country's prospects is multiplied by his influence over a single voter, who happens to be the leader of the opposition. As such, Papandreou is not entitled to act like any opposition member. He has a titular and constitutional role as prime minister in waiting. He owes it to the nation to make his professed beliefs his true ones. Instead, his weakness has allowed him to succumb to the slippery logic that separates means and ends; and made him an accessory to one of the worst influences ever to cross the threshold of Greece's parliament. Though the rioting students and their myriad secondary school extras will have been unaware of it, this leaves them in a particularly cynical conundrum. The parliamentary political parties of Greece are at an impasse. The voting public is increasingly disenchanted with all of them. Polls this year have shown high rates of indecision (between 10 and 20 percent) and none have indicated that either New Democracy or Pasok would win power outright. Higher approval ratings for Syriza are only a protest vote, not a vote of confidence, and newly formed parties such as the Greens and Neoliberals are still too unquantifiable to benefit. There is not a single national figure who truly inspires confidence and respect. Meanwhile, with two major scandals and a series of minor ones that have cost it four ministers just a year into its second term, the Karamanlis government is tottering. Smelling elections and a coalition, Synaspismos knows it is time to strike, and it is striking by politicising everyounger people - almost as though it is suffocating for a voter market as badly as they are suffocating for a good education and a decent labour market. Nothing good can come of more Syriza and more Alavanos. If Greece is losing its children it is because it has lost its adults. |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 22 December 2008 ) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||