|

|

Reign of Terroir: Wine Tasting in the Peloponnese

Not a wine-writer in the commonly accepted sense of the word, Peter Terosino puts his nose into the glass to find out that Peloponnesian wines can travel far

|

"Here," says George Skouras with a flourish, "let me show you a trick." He picks up an empty wine glass, holding it delicately by the stem and lifts it to his face. "This is how you should really taste wine."

Around him sit two dozen or so journalists and writers, one from as far away as Singapore, deep in the ageing cellar of the Domaine Skouras winery near Argos, abutting the plain where the Mycenaeans grew their grapes 3,000 years ago. Skouras, the boss, is a well-dressed, tall and imposing man and a confident speaker to boot, an Agamemnon of the vines. In his spotless "Thousand-Barrel Cellar" he has our full attention.

|

Journalistic noses plunge into wines

Journalistic noses plunge into wines

|

|

"First, empty your lungs of air." There is a series of stentorian gasps as we pick up our own glasses with samples of white Moschofilero sloshing around in them. "Then put your nose into the glass and begin inhaling very slowly." Journalistic noses plunge into glasses. "You'll see how well the aromas come out." We do as he says, and hey, he's right. Skouras Moschofilero enters our mental files as something worth trying again. And again.

That's lesson number one, in fact, of a stimulating three-day tasting tour of the North Peloponnesian wineries organised by the local growers and Greece's development ministry who shelled out the dough for three nights in the poshest of the region's hotels and all the free meals and wine we could consume - all to get word of Peloponnesian wine out into the wider world.

|

Now let me make one thing clear. I am not, in the commonly-accepted sense of the term, a "wine writer". I maintain a healthy disdain for those hacks who bang on tiresomely about wines with "breeding" and "expressiveness" and what goes best with what food and whatnot. Most wine writing is as phoney as a bunch of plastic grapes. Wine to me is something to drink occasionally on a hot date. Period. (I find something oddly inspiring in the words of a 4th-century desert monk who, when offered a glass of wine, said: "Take this death away from me.")

|

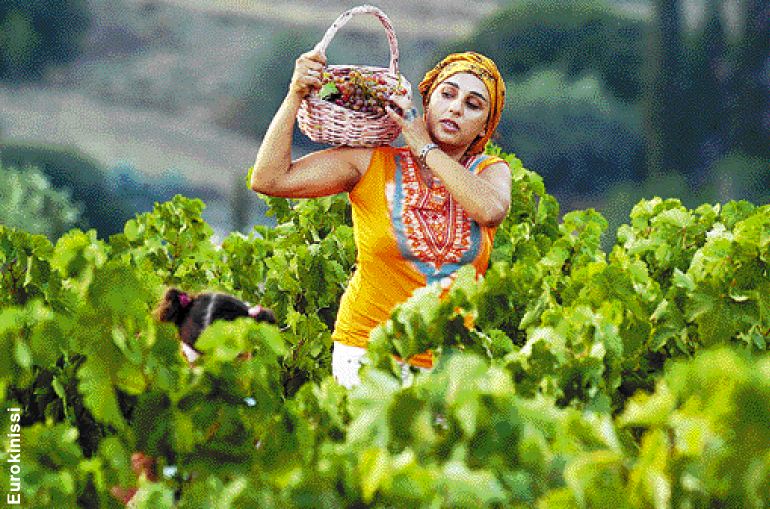

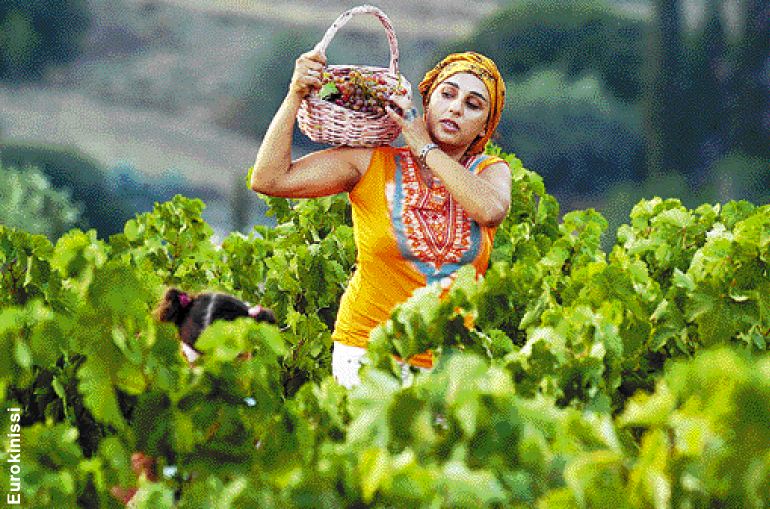

Harvest-time in the Argolid

Harvest-time in the Argolid

|

So it was with some inner embarrassment that, as I sipped dutifully at the 40 or so brands of plonk we all ended up sampling before staggering onto the coach back to Athens, I found myself coming up with precisely those phrases that I thought would never have the temerity to invade my professional writing lexicon.

So, now that I duly have donned the sackcloth (there's a Shakespearean pun there somewhere), here goes. If we're talking about what the winebibbers call "breeding," Peloponnesian wine hasn't got it. Not much Greek wine has. But does it really matter? In fact, if Peloponnesian wine - dry or sweet or in-between - is marketed cleverly, its brash, in-your-face characteristics may make a welcome change from the Beaujolais Nouveau and other soppy leftovers foisted on supermarket shoppers and hapless diners around Europe.

|

"The Peloponnese has huge potential for wider recognition," says Graham Blake, the international marketing director for Kourtaki wines. "For wine tourism, it could even beat the Napa Valley."

This reference to California's prime wine district is what the local winemakers love to hear. In fact, on the first day some of the more travelled writers among us are already unfavourably comparing the Napa Valley to the Nemea Valley. Greek wine, in fact, is like the Greeks. Brash and aggressive, a tad chaotic and rough-hewn, but to be accepted as it is, not as it ought to be.

|

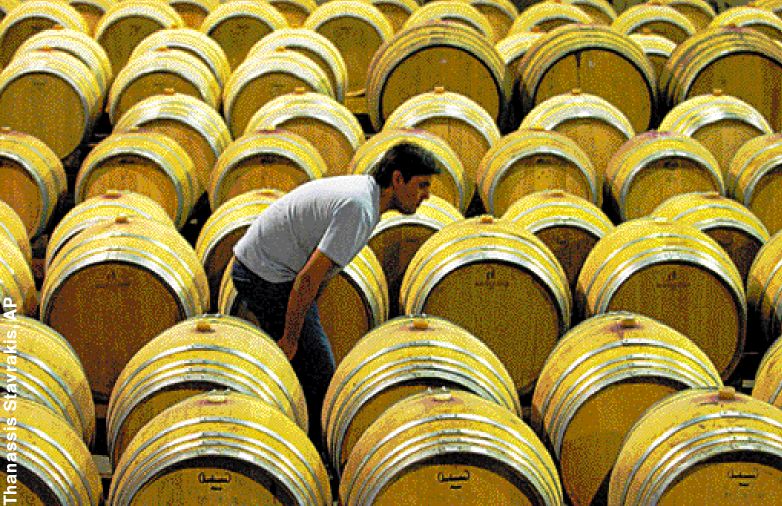

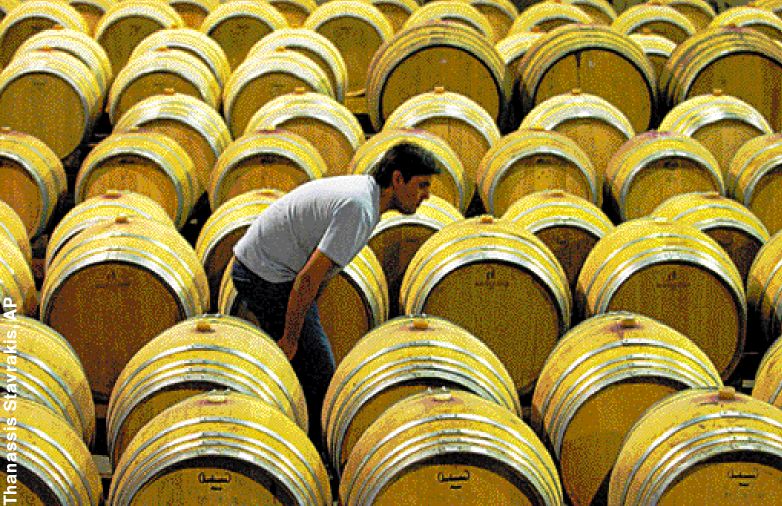

Inspecting wine barrels in Nemea

Inspecting wine barrels in Nemea

|

The previous day we had pottered around the ruins and wines of Nemea, an idyll of a valley just south of Corinth. The resident archaeologist, an American professor named Stephen Miller who set up the Nemea Museum and keeps it decent, told us of the thousands of drinking cups found among the ancient ruins - testimony, if any were needed, that even then Nemea wine was renowned. At the nearby Palyvos wine estate, we were told between bites of finger food washed down with Nemea red that the local soil and clay composition, plus the grape harvesting that is done predawn to keep the acidity low, accounts for the Nemea quality.

|

Wine specialists have a pretentious term for this soil business. They call it by its French term terroir, meaning not terror but "terrain", with a bit of a mystic connotation. More maybe than most forms of agriculture, viticulture binds people to their soil, perhaps because of the inebriatory power of the fermented result.

So from Argos we turn south past Tripolis to the southern frontiers of Arcadia. Since ancient times the Arcadians have been known as a rather rough lot, a reputation we see confirmed in the menu of the mountain taverna we stop at - gida vrasti, or boiled goat. So as not to impinge on the territory of this newspaper's food writers, I will say merely that it is an acquired taste.

|

Workers in the process of sealing

Workers in the process of sealing

wine bottles

|

As for the wine, a full-blooded (there I go with the jargon again) Agiorgitiko red (named after a mediaeval church near Nemea) helps wash down provincial meat dishes. It's what the trade politely calls a vin d'attitude, a wine that's supposed to give you a slight numbness at the sides of the tongue when you slip it down, the sign of a proper dose of tannin, we're told. The tannin also triggers saliva secretions that stimulate the appetite.

The best Agiorgitiko is made from grapes grown on the slopes of Mount Gymno at 1,800 feet above sea level. The average annual yield is some 5,000 kilos of wine per acre. Forty percent goes to foreign markets, where it averages about 7 euros a bottle. Related is the Skouras Dum Vinum Sperum, a chardonnay which goes for a whopping 17 euros. (The official brochure describes this oddly-named brand as "[not] over-ripe on the nose or fat on the palate". I guess you have to drink the stuff to know what that means.)

We hear the inevitable macho comparisons of wine with women ("you have to be gentle with it, but not quite trust it") mingled with scientific discussions of the merits of the newfangled screw-top bottle caps versus extruded cork. And ah, yes - it's not good to use wine that's been left over in the bottle for cooking. Always use fresh wine to cook, or your sautees will turn out lousy.

High in the foothills of Mount Mainalon, north of Tripolis, is the Spyropoulos winery at Mantineia. It's on the narrow plateau where in 418BC a superbly-disciplined Spartan force, singing martial songs by Tyrtaios, smashed an array of Argives and Athenians sent against it. These days Mantineia is the very image of rustic peace, where the budding vines drink up the spring sunshine at 1,800 feet, producing what the Spyropoulos estate calls a superior grape all round. Sampling the rich and aromatic Meliasto rose, one is quite prepared to believe it.

|

According to Yannis Tselepos, a Cypriot winemaker who now lives near Tripolis, "Arcadia is ideal for wine-growing because of its microclimate." Tselepos himself produces a spumante called Amalia, even a small quantity of which is startlingly effective at helping you forget your troubles.

What is striking about the Skouras and Spyropoulos wineries, and some three dozen others around the Peloponnese, is their newness. The headquarters are small villas, built to modern designs and painted in spotless pastel colours. The ageing cellars are clean and well-lit, the labs and bottling plants gleaming. A lot of money must have gone into all this. Three-quarters of all the new investment, in fact, is European Union-funded. Healthy wine profits account for the rest.

|

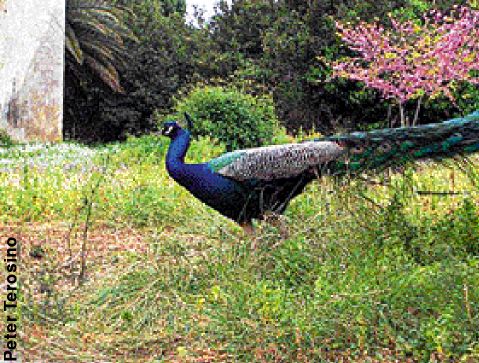

Living the free life on the Mercouri

Living the free life on the Mercouri

estate

|

We've saved the sprawling Mercouri estate at Korakohori, on a northwestern headland of the Peloponnese, for last. After a winding ride across the central massif and giving a ritual nod to Ancient Olympia, we disembark to the cordial smile of Vassilis Kanellakopoulos, the latest heir to the Mercouri family which has owned the estate since the 1860s. It's like entering a magical part of Tuscany. The old mansion has been abandoned, but among the orange trees and miniature ponds roam peacocks and fluffy cats, not in the least afraid of the mass of scribes clumping around the yard.

The weather now is closing in. A chill wind races in from the sea, and jackets are zipped up. Almost shivering, we sample about two dozen of the products of local producers who have sent their best wares. By now, few of our palates have any sensory distinctions left. Some tongues are black with red wine residue. And we're hungry. So as night falls we are taken to a well-appointed taverna in the centre of Korakohori. More wine here, of course, plus lashings of the best cheese pie any of us have ever tasted.

"Greek wine comes in a large variety, difficult to generalise," says Blake, who first came to Greece as a whisky salesman. "In Europe it's still a bit of an adventure, a risk of venturing into the unknown." Reducing this risk is what wine-tasting tours like this are all about.

John Chua, a Sinagaporean food and wine writer, rises from his table. "As someone who has come here from the other side of the world," he says, "and who has spent a lifetime tasting wines, I can assure you that, properly marketed, Peloponnesian wines can travel far." Just make sure, he added, to print labels in English rather than having them all in Greek.

The applause from all of us sounds thunderous. Then the clapping ceases, but the thunder continues. The floor begins to shake. Chandeliers begin to sway crazily. Rafters and walls creak and ripple. Earthquake! Heads dive under tables. Forkfuls of walnut cake dessert are dropped. Mercouri red is spilled. Gasps and shouts. A few (only men, I might add) make an undignified rush for the door. Who said terroir doesn't mean terror?

A full half-minute later the juddering peters out. Pale faces reappear. Someone laughs nervously. "That's a sixer for sure," a completely calm and smiling Kanellakopoulos says, meaning a 6 Richter jolt. He's not far wrong. Radios are switched on, cellphones whipped out. We learn we've just been clobbered by a 5.9 Richter quake emanating from Zakynthos, a mere few miles away. No one feels like eating any more, so the gathering is over. Chattering inanely, we pile back on the bus, to overnight at Patras before returning to Athens in the morning. The wine tour certainly had a sting in its tail, but I felt that any one of us would do it again. Even with the quake.

|

(Posting date 29 June 2006)

HCS readers can view other excellent articles by the Athens News writers and staff in many sections of our extensive, permanent archives, especially our News & Issues, Travel in Greece, Business, and Food, Recipes & Garden sections at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

. Readers enjoying these articles may wish to subscribe to the Athens News by visiting the website and following online directions at http://www.athensnews.gr.

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission.

|

|

|

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.HellenicComServe.com

|