|

||

|

Sikyon: Revival of an Ancient Site |

||

|

By Diana Farr Louis

A well-kept secret at the moment, the city that thrived in the northeast Peloponnese for some two thousand years before it fell into oblivion, is getting ready for an impressive comeback Supposing you were a quiz show contestant and the emcee asked you to name the artistic centre of Ancient Greece, you'd say "Athens, of course," wouldn't you, without a moment's hesitation. I know I would have until recently. It turns out we'd both be wrong. The correct answer is Sikyon, a city that thrived in the northeast Peloponnese for some two thousand years. Despite being caught up in the neverending power struggles between Argos, Corinth, Sparta |

Lake Stymphalia: more reeds than water and not a bird in sight |

|

| and Athens, not to mention Thebes and Macedonia in later antiquity, Sikyon's schools of sculpture and painting attracted the best artists from all over Greece. It also claimed to be the fashion capital as well as the birthplace of tragedy. A woman's wardrobe was not complete without white felt slippers from Sikyon. The city used to boast that its origins could be traced as far back as Prometheus, who bestowed the great gift of fire upon its residents. After stealing the precious element from the gods, he added insult to injury by deceiving them with the delicious aromas of roasting meat. He then persuaded the Sikyonians that the immortals had no need of other sustenance and they should save the best cuts for themselves. |

||

That of course is impossible to prove, but what we do know is that Sikyon was one of the earliest places in the region to work with bronze. In those days, in the 19th century BC, it was called Telchinia after the legendary Telchines, magician deities who were alleged to have invented metallurgy. A problem with charting Sikyon's progress through history is that it not only changed names at least five times but it moved around as well. Granted, this nomadic existence did not involve too much straying, but during Mycenaean times as Aigialeia, Sikyon was a beach town not far from presentday Kiato. Some time after that it retreated inland under the pseudonym |

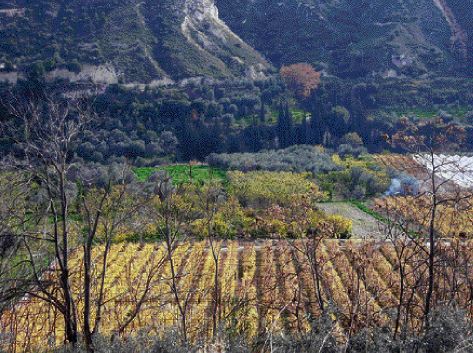

A view from the east side of Vassiliko, aka Sikyon, from the olive oil press, on an idyllic December day |

|

| Mekoni, which means Poppy. Subsequently and unaccountably, its vegetable identity shifted to Sikyon, a kind of gourd or cucumber (if not a prince of Attica who married into the royal dynasty). Even today, you will find few signs for Sikyon. All the locals know it as Vassiliko, and the site itself belongs to a third incarnation of the city founded by Demetrios Poliorketes in the late 4th century BC on a sloping plateau flanked by two rivers, somewhat higher than the Archaic-Classical town. The Macedonian king called it Demetria after himself, but the name did not stick and they changed it back after he died. |

||

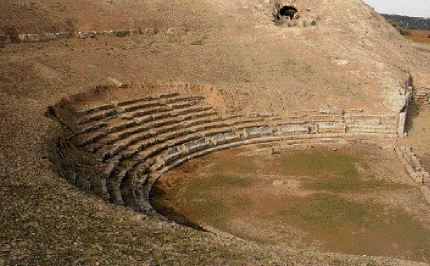

Until last September there would not have been much reason to seek out Sikyon. When I passed by some time in the late 70s, all I saw was a sizeable wreck of a theatre hollowed out of a naturally concave hillside. One detail lingered in my memory, though. Midway up, it possessed two vaulted passages, a late addition to Greek architecture, and I never forgot them. It seems they are unique, found in no other Hellenistic structure. So, I was excited when Sikyon made brief headlines in the cultural section of newspapers at summer's end. Its museum was reopening on September 6 after 25 years' delay and the photos accompanying |

The Hellenistic theatre, one of the largest in Greece, had 50 tiers of seats. Most of them are still covered by earth. The upper section was reached by two vaulted tunnels, the first of their kind in this country |

|

| the story reignited my curiosity. The building is part of a Roman baths complex. When Anastasios Orlandos, the noted architect/archaeologist who was also responsible for restoring the churches in Mystra, excavated it in the 1930s, he immediately envisaged it as a museum. It appears to have functioned at some point before his death in 1979 - the Blue Guide alludes to a few exhibits - but since 1981 its doors had been hermetically sealed. "What took so long?" we asked Christos Damatopoulos at the ticket booth. He shrugged his shoulders as if to imply "what do you expect from Greek bureaucracy?" And indeed the saga seems attributable to a combination of neglect, inefficiency and bad luck in the form of the earthquake that closed it initially. But one cannot find fault with the result. Sikyon's museum is a gem, truly worth the trip and the wait. Roman baths are usually eye-catching, with their faded brick walls and arched windows, and this is no exception. A path invites you into the courtyard, where gravestones, column shafts and capitals stand neatly ordered in rows and niches. |

||

|

|

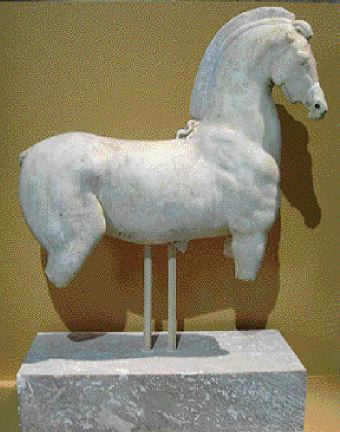

This horse statue was probably modelled on a piece by Lysippos |

|

| of Alexander the Great, and Apelles, the greatest painter of antiquity and court painter when Philip II, Alexander's father, ruled Macedonia. Sadly, we only know Apelles through his reputation and descriptions by contemporaries. Other than on vases, hardly any ancient painting has survived. And after the Roman conquest, Sikyon had to sell off whatever statuary was not looted to pay debts. But if the Sikyon museum elicits admiration today, just think how thrilling it must have been in its heyday. In the temple of Apollo, worshippers would have queued wide-eyed to examine Agamemnon's sword and shield, Odysseus' breastplate and a sample of Penelope's weaving, the kettle Medea scalded Pelias in, a couple of Argonaut oars and other similarly exalted relics. The list reminds me of when I saw the third forearm of John the Baptist in Topkapi. Sikyon itself spreads out around the conical-roofed museum. Apart from the large theatre, the remains (of the Hellenistic city) are not spectacular: temple and colonnade foundations, a double-terraced gymnasium-palaistra fronted by three fountains, a few courses of rounded ashlar masonry looking vaguely Florentine, an overgrown stadium. But, as always, the situation captivates. We scrambled over the tiers and packed earth that still conceals most of them, poked our heads into the vaulted openings (currently shored up by scaffolding) and sat in the VIP thrones in the front row. From there you look down on vine-covered fields and citrus groves to the cerulean gulf of Corinth with Parnassos, Kithaeron and Helikon, purple-veiled hulks, in the distance - stiff competition for any actors. |

||

One panel in the museum had mentioned a Frankish castle in the vicinity, but no one we asked could imagine where it might be. We threw a hasty glance at the Gothic-esque 13th-century church at the village entrance and drove east to find ourselves on a limestone scarp overlooking a narrow valley - an Impressionist's dream of golds, greens and browns. A pungent, familiar aroma wafted through the car window. Pickups mounded with olives were waiting outside the press just below us so we strolled in to see if we could buy some oil. Sikyon oil was celebrated in antiquity and is still excellent. One of the workers found us a plastic container and filled it with a petrol hose. |

Remains of the 13th-century Cistercian abbey of Zaraka |

|

|

He also pointed us in the direction of a rubble heap at the top of the road. "That's the Boudroumi. Built by the Franks." It was not worth a closer look. |

||

|

Get off the Corinth-Patras national road at Kiato (21km west of Corinth). Turn right after the overpass at the cemetery - you'll see the cypress trees - and before the A/B supermarket on the left. This is Odos Sikyonos. Follow it back over the highway. You'll be aided by signs for Vassiliko, Archaeological Museum and Archaio Sikyon, but keep your eyes peeled; the signs are elusive. If you have to ask, say you're looking for Vassiliko, the present name for Sikyon. The site and museum are about 5km from Kiato. The museum (27420-28900) is open every day except Monday from 8.30am to 3 pm. Photos by Diana Farr Louis |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 22 May 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||