|

||

|

The Coup at 40 Athens by Night November 1973 (Part 3 of 3) |

||

|

|

||

|

Forty years ago, a group of colonels suspended parliamentary democracy and press freedom in Greece. Their dictatorship would last seven years and end with the disastrous invasion of Cyprus. In the final installment of a five-week-long series of eyewitness accounts now out of circulation, we look back on one of the darkest periods of modern Greek history. This week, Kevin Andrews, a writer and journalist, describes the fall of the student uprising at the Athens Polytechnic in November 1973. The event triggered a counter-coup and marked the beginning of the end for the dictators

Wednesday, November 14th, 1973. I was just going to a movie. I was on my way to a movie. Trying to make the 8 o'clock show on the Number 3 trolley from Omonia Square, down Patissia Boulevard. |

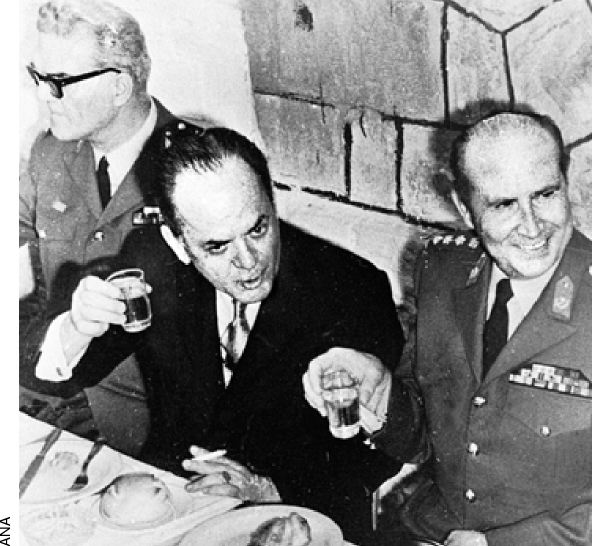

Coup leader Colonel George Papadopoulos (C) makes a toast with his feared cheif of the military policce, Bridadier Dimitris Ioannidis (R), and Lieutentant- General Phaidon Gizikis. Both men would betray him after the Polytechnic uprising, with disastrous results for Greece. His popularity weakened by the loss of life, Papadopoulos was ousted in November 1973 by Ioannidis and Gizikis was installed as president. The following year Ioannidis tried to assassinate Cypriot President Archbishop Makarios, prompting the Turkish invasion of the island |

|

| out in front, perched on the pillars of the entrance gate already placarded with slogans; all shouting out the words that nobody has dared speak publicly in Greece, and far less shout, for six and a half years, except on certain few occasions when the Police moved swiftly. I got off at the first stop. The demonstrators - students the lot of them - were pasting leaflets with their saliva onto the windows of the passing cars. A boy next to me was scribbling slogans at top speed in a school notebook. As he ripped the pages out I was able to take them from him and pass them through the windows of a trolley to a few outstretched hands. Some of the passengers stared down at us, others flashed the victory sign. Then he tore the last pages out of his book and slipped away. My turn now. I pushed through to the nearest kiosk and bought a copybook for 7 1/2. drachmas. Back in the middle of the avenue, dashing off slogans and flipping the pages over, I felt someone looking over my elbow (a fourteen-year-old, the age of my son) and was beginning to edge away when he said, 'What's that number you're writing there, Sir?' I stayed put. Number 114, the final article in the Constitution abrogated by the colonels who didn't know what it meant anyhow ('The safeguarding of this Constitution is entrusted to the patriotism of the Greeks'), had been a rallying-cry at the two student demonstrations violently suppressed by the Police earlier this year. 'And what's Thailand?' Then, after I told him how a student uprising - 'something like this around us here' - had recently toppled a Far-Eastern military dictatorship, neither of us had need of words. Both of us were busy, I dashing off the slogans (suggestions coming to us now from every side, and 'Haven't you got a marking-pen?') and he stuffing them through the car and trolley windows. Next morning [Nov. 13] the Number 3 didn't make its normal stop at the Polytechnic but one block further, at the National Museum. The avenue was now twice as packed [as the day before]. The Police - quite politely still - were turning everybody back who tried to cross over to the Polytechnic pavements. Thousands of demonstrators (by no means only students, and some of them must have been there all night) were chanting more slogans from the railings, all rhyming and all in the same relentless tetrameter rhythm: 'We haven't got enough to eat, today it's them we'll gobble up - Wake up, People, move yourselves, they're eating up the bread that's yours! - Down with Papadopoulos, a lunatic is ruling us!' Two other cries - 'Greece for Greeks in torture-chambers, Greece for Greeks in prison-cells' - parodied the senseless monotony of the Dictatorship's favourite motto, 'Greece for Christian Greeks.' We had got beyond that point; something had come out of a long hiding - something that would not fit back into Papadopoulos obsessive image of Greece as the patient in a plaster-cast. '... torture-chambers.... prison-cells!' Soon about five thousand people were taking up the cry in front of the National Museum, where pullman coaches were unloading parasols, cameras and tourists-as-usual at the entrance-steps. The demonstration had spread to the next block, the wide area of curving drives, lawns and open-air cafes, now loud with the chant of 'Education, Freedom, Bread - General Strike, General Strike - Let us not bow down to them! All of us together, at last it's Now or Never!' and innumerable other slogans on bits of paper in marking-pencil, faded ink or faded type littering by the thousands the streets of central Athens. 11 o'clock: five policemen made their appearance; five thousand of us scattered. As we ran I heard somebody wail, 'Only five of them!...' Five policemen only, walking rather rapidly in our direction, were enough to chase a multitude away. But I ran into a friend, with his sister and three of her fellow-students at the University; we drove in their car to Canning Square and bought eight loaves of bread, then drove back into Patissia Boulevard, handing them out to the crowds of students isolated on the Polytechnic pavements. 'Faster, Andoni, they've had time to write down Daddy's license-plates!' By 8:00 that evening the crowds around the School had swollen to the tens of thousands. Between dark cliffs poked with light the avenue was one great river of faces bright under street-lamps against black distances. And the rhythmic roar of voices never stopped; sometimes one group bursting into the National Anthem, another the rizhiko ballad from the White Mountains of Western Crete: 'When will the season of starry nights come round again, that I can take up my gun?' More placards were appearing too along the Polytechnic railings. The megaphones over the central gate gave out a loud hush, then announced that Salonica and Patras Universities had both closed down, with their students demonstrating in support of Athens. People pushing past each other said, 'Excuse me, please,' which you don't usually hear in an Athenian crowd: - a courtesy belonging to the generation in their early twenties and younger. Every so often somebody would call out, 'Down! Sit down!' and forty or fifty people would sit down in the middle of a street now empty of traffic, their arms around each other's shoulders, singing still. A man fainted, there was a cry of 'Make a circle, give him air!' and in an instant there was a wide space around him lying flat on his back on the asphalt, and someone fanning him with a newspaper. He was carried away, followed by calls of 'You're a hero!' The avenue belonged now to people who could do without public transport or the formalities of introduction. Everyone knew everybody else: the feeling was stronger than its own inherent danger. What about the spies, the plainclothesmen, the members of the EKOPH, or National Social Organization of Students, the enormous unseen army - some of them even busy studying thanks to a little secret pay - always there, in every imaginable quarter of university life, to watch, listen and denounce? 'How many of them must be packed in here among us!' I said unguardedly to one teenager, who replied hotly, 'If I recognize a single one of them, I'll kill him on the spot!' The third day, Friday, November 16th - people are now calling it Good Friday. From early morning the euphoria and excitement in the Polytechnic streets kept mounting to a degree that seemed to have no limit. It was quite unlike the frenzy that gripped Athens for several hours one afternoon in 1971 when the Panathenaic football team scored its victory over the Yugoslav Red Star, that promoted Greece to the European Cup Finals at Wembley. The release of pent-up steam that day was useful to the Dictatorship, which badly needed to provide a circus, and that had the Police out in full force to keep the multitudes moving fast along the streets, and the Army alerted in case of some change of wind. Today however one of the slogans was 'No more football!' The population had seen through that trick also. Meanwhile the megaphones kept the crowds of demonstrators in touch with what was going on inside the School: the meetings and discussions (to their supporters old and young a lesson in maturity, efficiency, open-mindedness, moderation, strength of purpose); the thorough organisation of the student-body and of the daily communal routine; the canteen already operating; the surgery in preparation for emergency; and the receiving and distributing centre for the donations - food, money, throat-medicines - now pouring into the building from a grateful people. All through the daylight hours groups of farmers, builders, actors, lawyers paraded before the School with the banners of their trade; lanes would open for them suddenly through the cheering crowd. Toward noon a band of countrymen arrived with a tractor, from Megara; they were followed by a chanting of 'This earth is yours and ours' - echoing a line from Ritsos' Romiosyni, echoing too the fury of some hundred farmers over the uprooting of 9,000 olive trees seven months ago, and the destruction of pistachio orchards, wheatfields, market-gardens and poultry farms, and the compulsory expropriation of their 2,500 acres by the Junta's richest backer, Stratis Andreades, for his oil-refinery at Megara. And then the news that the offices of the Nomarchy of Attica, in Stadium Street, had been taken over by construction-workers. |

||

Periodically there came a warning to the crowds: 'Placards with extremist slogans have been planted on our railings; this is the work of agents provocateurs. Do not let those people alienate you from us. Be careful what you read. Pay attention only to the messages approved by our Co-ordinating Committee. One word in particular will awaken bitter memories among some older of our supporters...' (The reference was to laokratia, or 'rule of the people', which had been a rallying-cry of the Communists and much of the Resistance in the streets of newly-liberated Athens at the catastrophic end of 1944.) 'This word, as well as all extremist slogans, we reject as having no connection with the student movement.' Meanwhile the students had set up their own radio station. Through most of the next 24 hours Athens listened to the voice of a young man or woman reading news and proclamations, with every few minutes the urgent feverish refrain: 'Radio Polytechnic - Radio Polytechnic - the station of the free and fighting students, the voice of the free Greeks in their struggle...' |

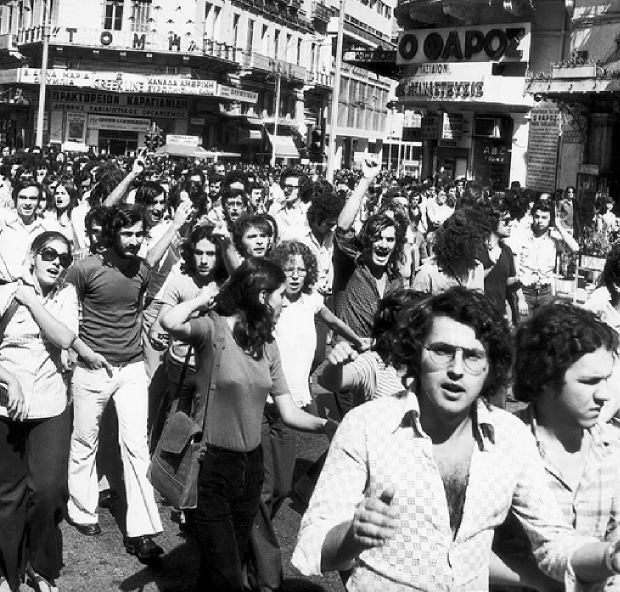

Students protest against the junta in the streets of Athens in the days before the Polytechnic massacre |

|

| Noon, neither overcast nor altogether sunny. A friend appeared in front of me - somebody I hadn't seen for months - and as we threw our arms around each other the people round us in the crowd laughed as if they knew us both. Then a curious sight: - students on top of pillars and railings twisting back and forth broad strips of sheet-metal to sweep flashes of reflected light up and down the apartment buildings opposite, to blind the cameras plainly visible in windows. If you couldn't distinguish police agents in the street you knew they were up there in any case, diligently making their photographic record of innumerable identities. One high balcony was spared; the students recognized the best young film director in Greece, and shouted his name triumphantly. My friend and I went up to say hello. Someone who opened the door asked for our names and waited for an answer from the balcony before he let us in. I think he got some of his film out of the country one of the next days before he was arrested and deported to the concentration camp on Yaros. Back in the avenue again - (where a new slogan, 'ESA - SS - vasanistes! 'bracketed the torturers of the ESA, or Greek Military Police, with those of the Nazi SS) - there passed through the sea of human beings swaying, chanting, raging, laughing and embracing, a soldier with the too-familiar blue band around his cap and the ESA insignia on his left arm. There was a murmur as he went by - not quite a growl, nevertheless enough to make him turn round and say with a pleasant smile (as at some bad joke of Fate), 'They put me in this job, is it my fault?' and everybody cheered him. 'Bad sign,' I said to my friend as she and I went off to get some lunch. How long in any case could all of this go on, the exultation and the solidarity? The students had been calling for a general strike, but the general strike had not occurred. We were both uneasy. True, there was no danger; the crowds were too big. At 5:00 I was exhausted and went home for a siesta, past the side-gate on Stournara Street where someone behind the railings called and handed me a list of surgical instruments. This I gave to a doctor-friend on my way down again at 8 o'clock. Hostilities, he said, had broken out and the Police had begun to use tear gas. Something I had never smelt. I went down by Solonos Street. No buses here now either. People were hurrying back up the street with streaming faces, handkerchiefs pressed to gulping mouths. I stopped one boy and asked what time the tear gas started. He croaked, 'They're - doing it - all - the time.' Time to wet a handkerchief. Someone in a cafe gave me a glass of water. A hundred students at the Stournara gate were still shouting slogans hoarsely through night air grey with gas and acrid with the smell of bonfires. The megaphones on the pillars were broadcasting instructions: 'Lemon-juice on the eyes. Or vaseline. Do not use water. Do not rub your eyes. Keep fires burning in the street. Keep fires burning.' Behind the gate they shouted, 'Doctors - we need doctors!' I ran back to Exarcheia Square, with someone running beside me, to find a phone booth. The two of us phoned till our stock of coins ran out, then continued in a cafe where money could be changed. The shopkeeper got angry with us for taking so long, and then with someone else trying to relay the same message. The shopkeeper told him to shut up; the man called him a police spy; the shopkeeper chased him out and grabbed him by the lapels, and a fight began on the pavement, but we didn't see the rest of it. Back at the Stournara gate I passed on the word that two doctors were already on their way. |

||

| As it turned out, both of them tried from 9:00 to 11:00 to get into the Polytechnic: it was the students themselves who wouldn't let them through. There were five thousand inside, university students, children from high schools all over the city, and a number of others who had got in before the gates were locked and it became clear to the Co-ordinating Committee and others keeping careful watch that many of these were police agents, spies, provocateurs. Tear gas had been let loose inside the Polytechnic area, and some of the students had already been wounded. Radio Polytechnic was now broadcasting appeals for priests as well as doctors. No priests came. I was on my way back to Exarcheia to phone more people and at least get the word around when I felt that familiar clap on the back in the dark: - three friends of mine running to their car. 'Come with us, Niko's buying food.' Halfway up Stournara Street a few demonstrators were trying to set up a barricade with bits of wooden fruit-crates and anything they could pick up in a vacant lot near by. |

Students gathered inside and outside the Athens Polytechnic gates in November 1973 shout anti-dictatorship slogans. Above the gates a banner reads 'THE LAND IS OURS'. It belongs to Megarian farmers who made common cause with the students after their olive groves were forcibly expropriated by the junta to allow shipping tycoon Yannis Latsis to build the Petrola oil refinery |

|

| Soon we were driving back with provisions. Some of these we passed in to the students at the side gate. The rest I dropped in through the small grilled window near pavement-level at the corner of Patissia Boulevard, that for three triumphant days had been functioning as the receiving-centre for supplies. Through the window they shouted up, 'Not any more food, we need medicines! Throat-medicines if nothing else!' There was no longer one massed crowd out in the street but only separate groups of people tending the bonfires and shouting slogans still, in unison with the young people gripping the railings from inside. Now, some time after 10:00, there was a huge new placard on the main gate: WHEN THE PEOPLE AREN'T AFRAID THE TYRANT GETS FRIGHTENED. The first ambulance arrived. (It took a long time coming.) Wounded students were carried out through the side-door and hustled in. I caught a glimpse of one bandaged head with a big red blob in the position of the eye-socket. I had lost my friends in the side-street: I was alone now, not responsible to anyone I knew. It was better this way: - just a wide avenue full of fires, and a kind of freedom in the dark. I crossed to the corner of Averoff Street. Fifteen people were huddling behind a furniture shop at the corner. Bullets began hitting the pavement a few inches from our feet. 'They're trying to get us from up there!' Government snipers had in fact installed themselves in rooms on the fourth floor of the Acropole Palace Hotel across the narrow street. The hotel itself had been taken over by the Army as its headquarters for the night. There were a few minutes of absurdity - perhaps when the individual is without a weapon absurdity takes over. None of us in any case had seen the slaughter one block down Averoff Street opposite the Ministry of Public Order three quarters of an hour earlier, nor did we see a girl, a Norwegian tourist on holiday, being shot dead beside the kiosk across the boulevard, and then carried into the hotel. 'Do-lo-pho-ni!' As the bullets crackled down the young people at our corner still had the energy or bravery or vapidity or whatever it was to shout up at the lightless windows, 'Murderers, assassins!' - still in rhythm, still in unison, as if the appeal to shame or conscience or some higher power could now halt the drift. As if words still mattered. |

||

Someone on a motorcycle charged down the boulevard; we shouted to him not to cross the line of fire (bullets were hissing past from down the street), I think he made it, though perhaps not at the next intersection. Then, for all the shouting, five out of our group tried, one after the other, to dash over to the other side. The first got a bullet in the eye; three drew him back by the heels, picked him up and rushed him across the avenue. Another stepped out and was shot in the stomach; three days later I learned he was dead. The next fell, with a bullet in the wrist. And yet a fourth, for all our pulling, would run out: he was shot in the throat. They carried him into the Polytechnic surgery, and the radio announced his death an hour later. The pavements gleamed with blood - how much of it can empty out of a human body in a space of seconds! Three of us were left now at the corner. Still one would put his leg out to dash across - a bullet hit him in the ankle. As he |

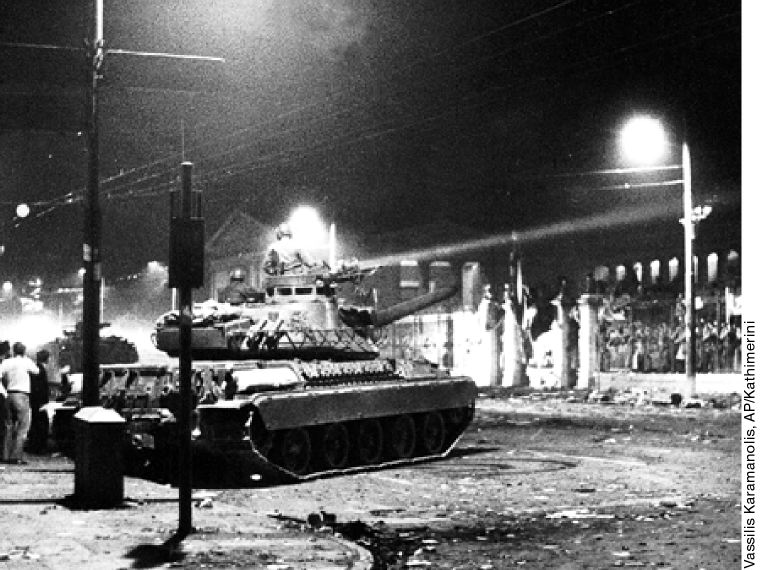

An army tank prepares to roll into Athens Polytechnic on November 17, 1973. The terrorist group November 17 takes its name from this event |

|

| collapsed the other one and I hoisted him up and, slithering over the asphalt, with the hot gush of his blood pulsating over us, lugged him across the boulevard to an ambulance where he was stuffed in top of a lot of others. Again through the tiny window a dizzy glimpse of bloodstained bandages, figures writhing, others in white smocks shifting bodies into place. I didn't know that the drivers of certain ambulances were also police agents. What happened to those wounded and dying is anybody's guess. Out here now in the almost empty street the tang of combat in the nostrils: the smell of smoke, gas, gunpowder, and no more alternatives. Years of collective boredom had given way to a few minutes of individual responsibility - a wild quiet concentrated crystalline feeling of release. It would have helped if I had known how to save someone, the way many people did that night, but all I could do was move about, still quickly, perhaps reach someone in the foreign Press, to help get the word out of the country fast. As if words mattered. But how? And who? And where was there a telephone? The buildings on the avenue had all blacked out. Yet over on Stournara Street (still some demonstrators there!) one lighted window shone. I went up in the lift and pounded on a door. It opened a crack on the safety-chain, and an elderly man poked his nose out. I asked for his phone. 'No. But give me the numbers and I'll do the calling.' I scribbled some numbers and the names of three well known Athenians, on purpose to impress him. It worked. 'Ah! Mr -? And (who is this?) Mr -. Yes, certainly,' he said, and closed the door. But he made the calls. One floor down I pressed the buzzer of another flat. A young woman opened the door. Somebody behind her cried, 'Your leg!' 'It's all right, it's not me. Let me phone.' Someone in the hallway said as I pushed in, 'Who are you?' I risked telling my name. 'Not possible!' he said. 'D - has often told me about you, and A - was going to bring me to your place once. Here, telephone!' I called one friend. He recognized my voice and gave me the number of a foreign correspondent. He had gone to his cameraman's hotel, but while I told his wife what I had seen I could hear her telex sizzling like fried eggs underneath my narrative. |

||

'What can you see now?' she asked, and I shouted her questions to the others standing in the window, looking down onto the Polytechnic area out of the darkened room. 'How many ambulances have come?' 'Do you see signs of Police or Army formations massing for a raid?' 'And do please excuse the inconvenience.' 'It doesn't matter.' As I hurried out I caught a glimpse, framed between sliding panels, in the next room, of four older people seated around a table, playing cards. |

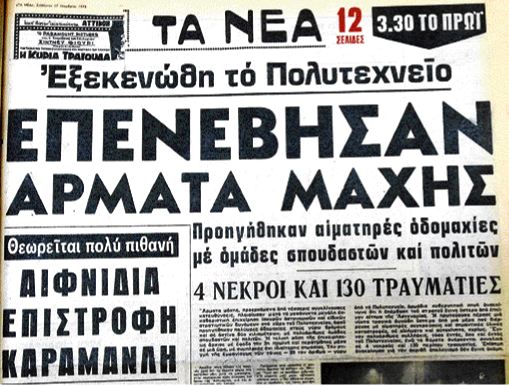

The front page of Ta Nea the morning after the killings. The surtitle reads "The Polytechnic evacuated" and the banner headline "Tanks intervened". The subtitles read "Street battles with groups of students and civilians came first" and "4 dead and 130 wounded". The casualty list would climb, but a definitive tally has never been made |

|

|

So down into the street again. Out into the vile thick stinging air, under the streetlights grey with the smoke of bonfires burned out. Stragglers in the avenue, no longer shouting. Shouts still coming from the thousands massed inside the Polytechnic forecourt. One husky voice still frantically calling news and proclamations over the megaphones against a distant roar.

'I'm asking because we were out on Alexandra Boulevard half an hour ago and definitely saw troop formations.'

'No. Nothing at the moment.''All we can see here is a few groups of demonstrators.' 'Are the Police obstructing the movement of the ambulances?' 'Yes. They're throwing tear gas into some of them.' She gave me the cameraman's number, and I called and urged him to get as close as he could. 'But surely it isn't possible to go out into the street now!' Armoured cars diverted off the avenue were hurtling along Third-of-September Street one block down. Then the farther bus was rolled over like an empty bottle. The Polytechnic megaphone was calling into the street, 'Friends, supporters, do not abandon us now!' After that everything was noise. The tanks came thundering and rattling and squealing down the avenue. Ground, buildings and a few shreds of reason shook in the same general convulsion. The young people around me were crying out, 'There is no danger! They cannot fire on us, they are our brothers - soldiers, children of our people!' |

||

And one last innocent called out, 'We'll win them over with truth and justice!' 'Idiots!' I shouted. 'They're not your brothers! Do you think they care for truth or justice! Six years they've been trained to kill. Run!' Nobody moved. And I too had to see what the tanks would do at the last minute. I didn't get the chance. The tanks and armoured cars roared past us fast and steadily - deafening immense black blunt interruptions, one after another like some final measurement of time. The soldier upright in the eighth turret waved to us. From round the corner a cataract of troops - helmets and lifted clubs - fell on us. Panic swept us in a body straight back into the first apartment block. Into a small bright-lit corner between lift and stair. One or two may have struggled up a few steps before they were caught backwards under the lightning web of clubs that knocked us to the floor, down low where boots could aim directly into faces, kicking from far back, stamping from above on necks; and the clubs a zigzag crackling of yellow varnish down, up, down, up, down onto immobilized and tumbled bodies. |

Police wash the blood and muck from the gates of the Polytechnic on the morning of November 18. A precise tally of the number of students and others killed has still not been compiled |

|

Little faces, dark under the helmets, not recognizable as human. I tried to duck and shield my head under one arm but the first blow broke a bone in my hand. I ducked again under the other arm, but it was wrenched aside and clamped outstretched; and then just clubs crashing down onto a skull: - thunderclaps, regular, methodical. Now me at last. Not just that picture in the newspaper. Not just me looking at a newspaper. And for some reason no pain either. Nothing (it was still possible to think - professional torturers perhaps forget this element) compared to the tearing humiliation of all those canings in an English boarding-school before the War. Marvel at the hardness of this bone, this brainpan, marvel at what it's possible to bear! Then one fist grabbed me by the hair and yanked my head back. Then one slug of a club on the throat. No sensation. Vision blurred. I was standing up and lowering myself by the wall down three steps toward the door. Where were all the others - the victims, the attackers? But it didn't occur to me to wonder why I alone was left here. Nor did I notice what was missing from my pockets: my residence-permit, with a foreign identity that might look embarrassing if I was dead (conveniently unscarred but with a broken windpipe), and a purse with some money in it - but money is neutral and, judiciously appropriated, incriminates no-one. I don't know how much time had passed. Outside in the middle of Stournara Street again a bystander (who was he?) said, 'Blood's running down your head.' Yes, fingers wet with it. I turned right into Canning Street, left into Solomos. A car was driving very slowly past - a taxi! I got the words out, 'Take me with you.' 'Hop in front!' There were others in the back. The taxi drove on, then slowed down as we approached the corner of Exarcheia Square. Thirty or forty police officers were standing there under the dim light, the badges of rank showing silver on their black uniforms. The taxi stopped. They opened the door, and an officer tugged me out by the arm. 'Where were you! Where! Where were you!' The taxi was driving quietly away - mission accomplished. A moment's indecision: the terror of choice. What could I pretend with all this blood? They were pulling my pockets inside out and punching me in the face. One of them pulled out a leaflet I had picked up in the street, marked DOWN WITH THE LUNATIC. I reeled back from a sock in the jaw. 'But what have I done to you?' I said, trying to play a role. One of them gave me an upper cut, but again for some reason it didn't hurt, and I tried to say in the quietly outraged tone of a respectable personage in a case of mistaken identity, 'What sort of behaviour is this?' Between the punches (yes, the fists were human but my face was like a block of wood) I warned them I had epilepsy and it would not go well for them if... But now two groups of officers had me by both elbows; others were knocking me on the head and giving kneeblows in the genitals, until the pavement rocked and cracked on my head with a clatter o f stars, and they picked me up and threw me from one to the other (middle-aged, with looks distorted by memories of the Civil War, and all of that so long ago, is there no end to vengeance!) back and forth, socking and spitting out the words, 'Bugger - peasant - peasant - bugger - swine!' |

||

| I was too dizzy from concussion to put up a resistance to the knuckle against the nose and the boot smashing lip against teeth, or the grinding of teeth into the asphalt, or the crash of the boot on neck-vertebrae, or the showers of spit and lick of phlegm hawked out of their mouths, or the same boot pounding in the groin. Friends said afterwards, 'Why didn't you tell them you were a foreigner!' I had quite forgotten. When it came to an end, there was just time to pick up my house-keys before the policemen flung me out into the middle of the street (thud of asphalt on the shoulder), yelling, 'Out of here, you filthy scum!' There was a splutter of machinegun-fire across the square. By now the attackers would have broken - after ten minutes - the truce agreed to for all the besieged to get out of the Polytechnic within half an hour. By now the first tank would have broken down the central gate, mangling its railings and squashing a Mercedes parked behind one of its pillars as an attempted buttress that, as it was dragged along under the treads, crushed the legs of a girl who had been standing on top of it, shouting her defiance at |

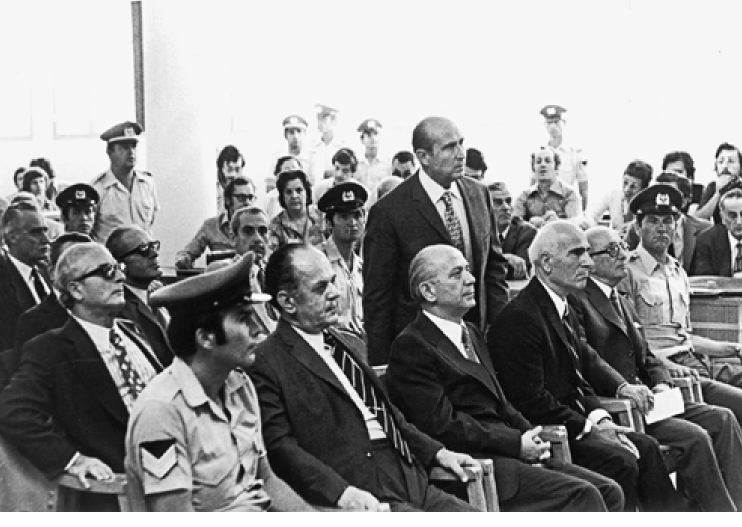

The dictators on trial in 1975 (front row L-R): George Papadopoulos, Nikolaos Makarezos, Stylianos Pattakos. Standing behind them is Nikos Ioannidis, who unseated them in an internal coup after the Polytechnic killings, for which, as chief of the military police, he was largely responsible. The three instigators of dictatorship were given death sentences, commuted to life in prison, largely because of their handling of the student uprising. Ioannidis was handed a sevenfold life sentence |

|

| the engines of destruction and the law. By now too the students (who till the last minute had stood clinging to the railings, calling to the tank guns and the rifles and the submachineguns taking aim, 'We are unarmed, you will not kill us, you are our brothers') would have been surrounded in the forecourt by the first Commando units, telling them to get out quickly by the other gates before the Police entered in force and drove them out, to be killed and wounded in the streets. On the other side of Exarcheia Square, as I was picking myself up, a group of Police were knocking somebody to pieces while another band (one of them had his revolver out) were chasing people into a dark street, shouting, 'Don't let them get away! Kill them!' Behind me a clatter of boots approaching. Panic again. I broke into a run, stumbling. Someone else caught up with me; I tried to outrace him to a street across the square where an old couple in the door of their apartment block were letting themselves in fast. The two of us shoved in before they closed the door. I fell against the stairs in the dark, something had happened to my leg. 'Shelter me, for God's sake, they're killing people!' 'Hush, please, don't wake the neighbours,' The old couple were pressing the button for the lift. 'I can't go out, I've been beaten up, they're killing people! Take me in!' The other person in the dark said, 'Come with us, we've got a car.' And the two old people said, 'If you need anything, this young man can help you,' as they backed into the lift, shut the door on us, and floated up to their own private safety. I ran up five flights of stairs, trying to find where they had gone, at the same time too confused and frightened to knock on any door. The other person came after me, took me by the hand and drew me down again, helping me not to fall, while I protested senselessly, 'Look after your own life! No, no, let me go, I'm not going out into the street again!' 'Come - come - we can get you out of here in a car. We've got a doctor.' And when we reached the ground floor: 'Wait here.' He went to the door and looked out. Twenty metres away stood a policeman with a tommygun, facing in our direction. A few minutes later he looked out again. Two policemen stood at the corner with their guns facing the other way, toward the Polytechnic. 'Now - quick!' We crept out, hugging the wall; he leading me by the hand, as far as a parking-lot where his friends were waiting in a car. We've got someone wounded,' he said, lifting me into the back seat on top of another man and two girls who burst into tears. We drove off at full speed. On the other side of Lykabettos Hill, as we drove past the Naval Hospital I began to get frightened (where were they going?) and told them to drop me off in Deinokratous Street, I had friends living near by. |

||

But they said, 'We can't leave you,' and we turned down Lachitos Street toward the American Embassy. There at the corner of Queen Sophia Boulevard, opposite the headquarters of the ESA, were thirty policemen, but the car had a foreign license plate, and they didn't halt us. We drove past the Hilton Hotel and finally reached their quarter where they helped me up into a three-room flat. Here one of them, a doctor, clipped the hair round the gash in my head, washed it and covered it with sticking-plaster: dark, so as not to show. 'Come to my clinic when it's day, I can cover you,' he said. 'Now you must lie down, we'll make up a bed.' But I was curious to get a better look at my rescuers. They were all Cypriot students. Returning from the Polytechnic earlier that night, they had seen tanks stationed along Mesoyion Street, near the Odeon Cinema. Between midnight and 1:00 they had heard the student radio appealing to the foreign embassies to send observers. No embassy replied. The Cypriot Embassy |

Deputy Press Minister Spyros Zournadzis escorts a press corps around the Polytechnic campus after the suppression of the uprising. Here, he is demonstrating the radio station students had put together from laboratory equipment |

|

|

too had closed down for the night. They heard the tanks rolling down Mikras Asias Street from the direction of the Goudi Army Camp while the Polytechnic radio was broadcasting more appeals for hospital supplies. Then they filled their car with medicines out of the doctor's store, and at 1 o'clock drove off. Two tanks were racing down one street in front of them, while watchers on balconies shouted down, 'Shame! Murderers!'

Finally in a vacant lot they left the car with the medicines still in it, but as they came down Valtetsiou Street students on the run said, 'Don't go any further, they're shooting to kill!' Nevertheless they continued to Exarcheia Square, and there had seen me being beaten up on the other side. When I was running into Valtetsiou Street a band of Police had sprung at them out of the darkness. Four reached the car; the last one made it into the block of flats with me. Now, far away and in comparative safety (the Police were attacking in many parts of town, and light through the shutters could attract attention) I could not stop talking. But they were hanging on the radio; a second student station operating in the vicinity of Plateia Amerikis had gone on the air the moment the Polytechnic fell. 'Calling Polytechnic, calling Polytechnic. Will Radio Polytechnic please answer?' While yet another programme pretending to be the voice of students, was emitting provocative extremist slogans, this second station continued broadcasting till well into the day, when the survivors of the holocaust - those who didn't reach the private flats and secret clinics (some ready ever since the armed assaults against the University in February and March) - came out again in large numbers and marched down Patissia Boulevard and the streets around the Polytechnic, shouting always in tetrameter, 'Last - night - they killed your - children... Come out into the streets yourselves!' Several who came out that day were killed. Many more were wounded: isolated bystanders doing nothing, only gazing at the passing tanks till they were shot. The less the others now were listening, the more I was obsessed with the urgency of telling my own misadventures, as an example of a much larger picture, to the reporter and his wife who had said over the phone they could be reached till 5:00 am; for security reasons they would then have to be inside the Government Offices, waiting for the Premier's press conference. It was now 3:30. Yet calls to foreign journalists, with their well tapped lines, could be traced straight here. One of the boys went out to a public booth to see if it was safe. He was back quickly. 'They've caught three Cypriot students in the next street. You can't go out looking like that.' Then in my stupefaction, not realizing how much I was endangering the lives of others for a matter of no great importance, I got them to phone a friend of mine, someone who had signed one of the pages of history during the German Occupation, whom I knew I could call on in any need or danger. 'Don't stop at the door to ring the bell, someone will let you in immediately,' they told her, and she was there in half an hour with a taxi. Twenty minutes later, driving through a black and silent city, we were in the quarter of the foreign embassies, where the Police were not likely to be shooting indiscriminately, and I was able to telephone my story, propping myself against a kiosk miraculously open at 4:30 in the morning. After that, on a high floor and behind doors locked on any more excursions, it was possible at last - having thrown my clothes into cold water to soak out the blood - in a darkened room and the abandon of collapse (no more hard emotionless concentration on survival), to meet the devil face to face: - the full force of the hatred that had penetrated deeper than anything I had breathed in with the bullet-streaked air, or slid on, or rocked under. Early experiences of combat, night-reconnaissance or enemy artillery were as nothing compared with the spirit that had been abroad this night. No way now to prevail against convulsive sobbing until sleep filtered thickly through it with daylight showing through the blinds. Later that morning I noticed the pain and swelling in my hand. Below us, in the sunny autumnal streets, rifle-fire even here among the foreign embassies and private palaces, in order to keep people indoors, away from the tank movements all over town, out of sight of an army gone berserk (it was the Army's turn now, the Police had faded out of the picture somewhat), killing and wounding pedestrians, anxious shoppers, housewives, small children, throughout scattered areas of Athens till the afternoon of Sunday... Away also from any approach to or sight of the Polytechnic itself, where the incoming Army units had been busy until dawn wrecking the place systematically and covering the walls with anarchist slogans, for effect, until the fire-engines came to hose the streets and wash the blood into the sewers. When the stage was set, the Information Minister Zournadzis took a party of foreign officials and journalists around the wrecked and bullet-riddled Polytechnic. His way of countering reporters' questions was to read out to them an article by Max Beloff on student unrest in Venice in the year 1939. But why, asked the reporters, had the Government not jammed the student radio? 'Because,' said Zournadzis, 'the Polytechnic had its own power station and we had to respect the territorial immunity of University buildings.' At 10 o'clock we listened to the announcement by General Zagorianakos, Commander-in-Chief of the Army: martial law re-imposed, a state of siege, full preventive censorship, and a curfew to begin at 4:00 in the afternoon. As in April 1967, a long night would be needed for arrests to sweep the city, and for the wounded to be dealt with - sometimes not by doctors but by armed policemen - in the wild congestion of the hospitals, and for the bodies of the dead to be sliced up in the morgue for autopsy or transported to cemeteries under close military guard. Certain noteworthy news items would occasionally interrupt the cheery martial music. We learned that Markezinis (who in the years of parliamentary democracy had never polled more than 3% of the national vote but was now enjoying a 6-week Premiership in Papadopoulos' final ploy - a civilian mask to the Dictatorship) had at the last minute called off his dawn press conference; questions were better left to the ravings of a Zournadzis. Markezinis went later to the Athens Pentagon to congratulate the Armed Forces in a tone similar to one of the Government communiques: - 'The enemies of the nation are unrepentant and do not want elections. The Ministry of Public Order called on the assistance of the Army. This assistance resulted in the bloodless evacuation of the Polytechnic...' Kapsaskis, the Government Coroner, announced nine dead, Zournadzis praised 'the lofty virtues of martial law'. And then: 'Whoever is discovered harbouring anyone not of the immediate family will be courtmartialled' - a way of driving the wounded into hospitals for identification. Finally, as to be expected, Papadopoulos: 'In profound awareness of my responsibilities to the nation and to history -' But we had been hearing this for nearly seven years. We turned the radio off. Past 3 o'clock; my hand swelling fast. To have it X-rayed at a hospital meant giving information - wounds, circumstances of infliction, name and address. But who might already be scanning the data on my residence permit and writing it all down? A series of carefully worded phone calls led me to a radiologist who, I was assured, would ask no questions. He drove a long distance to meet me in his consulting room, while the minutes ticked by. The X-ray showed a diagonal break across the hand I had ducked under. 'When you get home just take a piece of cardboard and bend it round your wrist and tie it up with string, it should be all right till Monday.' It was a slow pull back to my own district on foot. Not a taxi in sight. Two cars only, and when I hailed them they went by at top speed. I got home with a minute to spare, bolted the front door, and closed the shutters quickly. *Kevin Andrews worked in Greece as an author and journalist until his death in 1989. This passage is reproduced with permission from his book Greece in the Dark, published in 1980 |

||

|

|

||

(Posting Date 16 May 2007) HCS readers can view other excellent articles by this writer in the News & Issues and other sections of our extensive, permanent archives at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||